Beginnings

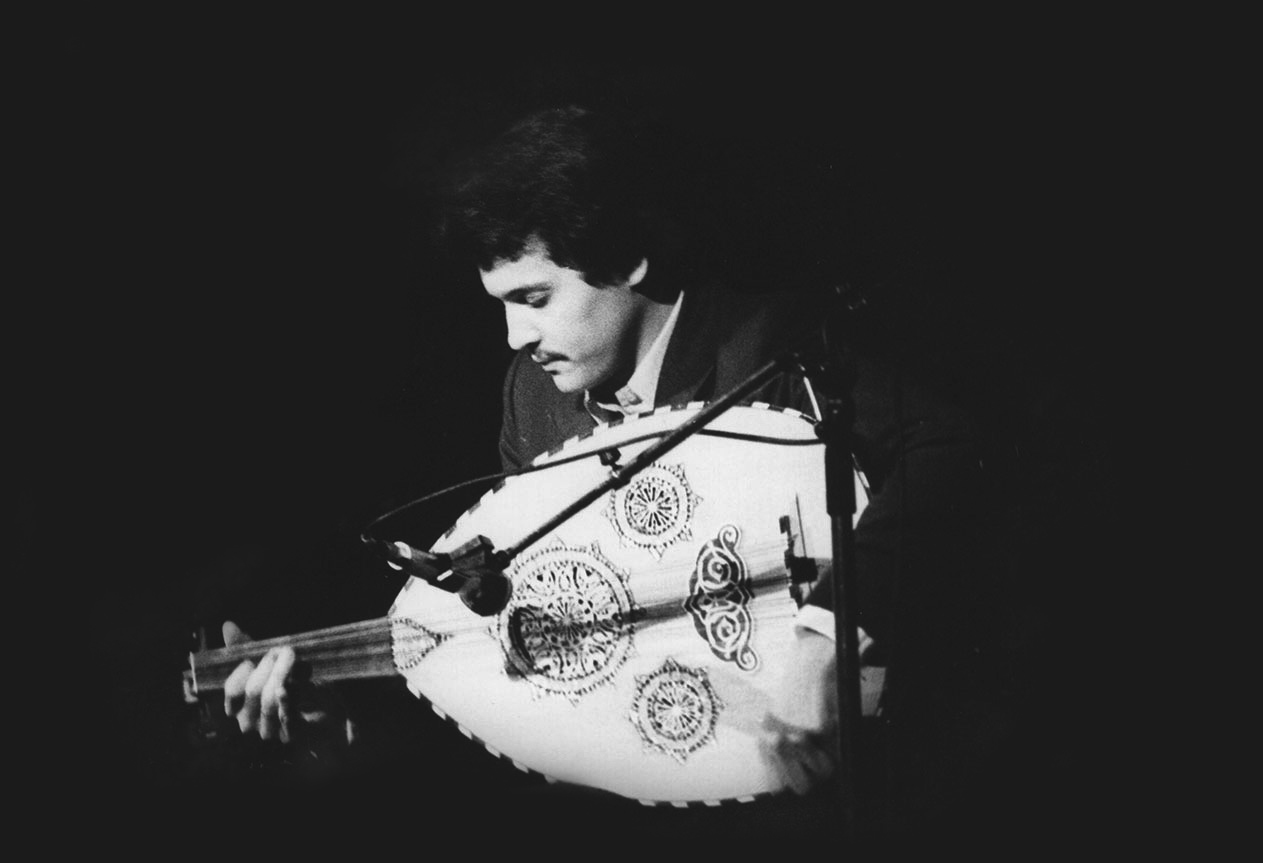

Anouar Brahem was born on October 20th 1957 in Halfaouine, in the Medina of Tunis. Encouraged by his father, an engraver and printer but also a great music-lover, Brahem began his studies of music and the oud at the age of ten, when he attended the Tunis National Conservatory of Music; his principal teacher was the great oud master, Ali Sriti. An exceptional student by the age of fifteen, Brahem was playing regularly with local orchestras; at the age of eighteen, he decided to devote himself entirely to music. He went back to Ali Sriti who followed the traditional master/disciple relationship by receiving Anouar at his home every day for four consecutive years, transmitting to him the subtleties of the maquamat (the complicated modal system of Arab classical music) and the taqsim.

Little by little, and in spite of the fact that his education was encouraging him to serve the tradition of Arab classical music by bringing him to such a high standard of excellence, Anouar began to broaden his field of listening to include other kinds of musical expression from around the Mediterranean Basin, even extending his curiosity further so as to include Iran and India and their music, then jazz. "I enjoyed the change of environment," he says, "and I discovered the close links that exist between all these kinds of music."

So Anouar Brahem increasingly distinguished himself from a musical environment almost exclusively devoted to vocal music and largely dominated by light music. He wanted more than to perform at weddings or join one of the many existing ensembles; he considered them anachronistic, and the oud was usually no more than an accompanying instrument for singers. Brahem was convinced that his instrument, a favourite of Arab music, should be given pride of place, and he began giving instrumental concerts and recitals to Tunisian audiences, often playing the oud solo. By now he was also interested in composition and began writing his own pieces, rooted in tradition but already integrating quite spontaneously certain elements from other oriental or Mediterranean musical traditions. He recorded his first cassette, produced at his own expense, with the percussionist Lassaad Hosni.

The Eighties: Tunis/Paris, Paris/Tunis

A loyal public of connoisseurs gradually rallied round him, and the Tunisian press gave him enthusiastic support. Reviewing one of Brahem's first performances, critic Hatem Touil wrote, "This talented young player has succeeded not only in overwhelming the audience, but also in giving non-vocal music in Tunisia its claim to nobility, while at the same time restoring the fortunes and reputation of an instrument much in need of revival: the lute. Indeed, never has a lutenist produced such pure sounds or concretized with such power and conviction the universality of musical experience".

In 1982, Brahem had a strong urge to make new encounters with musicians from other backgrounds, so he moved to Paris, that most cosmopolitan of cities. He remained there for four years, collaborating with Maurice Béjart for his ballet Thalassa Mare Nostrum, as well as with Gabriel Yared as the soloist for Costa Gavras’ film Hanna K. But the core of his work concerned composition, particularly for the Tunisian cinema and theatre, which gave him the possibility of experimental work; his orchestrations now systematically included techniques and instruments outside the traditional scope of Arab music, especially when he called on jazz musicians.

In 1985 he returned to Tunis to continue his research into compositional material. The first performance at the Carthage Festival of his ambitious work Liqua 85, brought together many outstanding figures from Tunisian and Turkish music and a smaller group from French jazz, including Abdelwaheb Berbech, the Erköse brothers, François Jeanneau, Jean-Paul Celea, François Couturier and others. Not only did this occasion bring him an appreciative audience that included young Tunisian musicians, where it was generally agreed he was one of the most innovatory and influential contemporary Arab musicians of his generation; but also, at the age of only twenty-eight, he was awarded the “National Music Award”. He remains the youngest musician and composer ever to have received this distinction.

In 1987, Brahem came back to Tunisia on a long-term basis, and was appointed Director of the Musical Ensemble of the City of Tunis (EMVT). Instead of preserving the existing large orchestra, he restructured it into formations of varying size and gave EMVT new orientations: one year the tendency was for new creations, and the next more for traditional music. The Ensemble’s main productions were Leïlatou Tayer (1988) and El Hizam El Dhahabi (1990), in line with his early instrumental works and the main axis of his research. In these compositions, he remained essentially within a traditional modal space, although he transformed its references and reordered its hierarchy. Following a natural disposition for an osmosis absorbing Mediterranean, African and Far-Eastern heritages, he also ventured from time to time onto new terrain, exploring other forms of musical expression and sensibility stemming from European music and jazz.

With Rabeb (1989) and Andalousiat (1990), Anouar Brahem returned to classical Arab music. Despite the rich heritage transmitted by Ali Sriti, and the fact that this music constituted the core of his training, he had in fact, never performed it in public. With this "comeback" he wished to contribute to the urgent rehabilitation of this music. He put together a small ensemble, a takht, the original form of the traditional orchestra, where each instrumentalist plays as both a soloist and improviser. Brahem believes this is the only means of restoring the spirit, the subtlety of the variations and the intimacy of this chamber music. He called upon the best Tunisian musicians – Béchir Selmi, Taoufik Zghonda – and thoroughly researched ancient manuscripts, taking rigorous care over transparency, nuances and details.

With Ennaoura el achiqua (1987), Brahem presented for the first time ever something that would match the eclectic and innovatory aspect of his music: a performance of song resulting from his association with the poet Ali Louati. In this exploration of vocal music, and despite its difference from the commercial trend of the time, he revealed a desire to reacquaint himself with elaborate classical forms such as the Qassid, following in the footsteps of Khemais Tarnane, Saied Derwich, Riadh Sombati and Mohamed Abdelwahab, whilst venturing onto the terrain of the “chanson à texte” of popular inspiration, sung by Brel, Ferré, and Brassens, of whom he was already a great admirer. Ennaoura el achiqua was a marginal work which went against the grain, nevertheless it had considerable impact on both press and public.

Ennaoura el achiqua was not to be his only incursion into the field of song. He would return to it occasionally, either in film music or in association with a singer, and often with the complicity of Ali Louati. For instance, he collaborated with Nabiha Karaouli, whom he revealed to the public, and also Sonia M’barek, Saber Rebaï, Teresa de Sio, Franco Battiato and Lotfi Bouchnak, who sang ‘Ritek ma naaref ouin’, composed in the spirit of an "imaginary folksong", and which, in an ironic twist of fate, became extremely popular, a must at wedding celebrations in Tunisia…

In 1988, playing in front of an audience numbering 10,000, he opened the Carthage Festival in the Roman theatre with Leilatou Tayer. The newspaper Tunis-Hebdo wrote: "If we had to elect the musician of the 80's, we would immediately choose Anouar Brahem".

The ECM Years

In 1990 he decided to leave the EMVT and embarked on a tour of the USA and Canada. It was on his return that he met Manfred Eicher, the producer/founder of the German label ECM Records in Munich, and their meeting resulted in a fruitful collaboration which undoubtedly marked a major evolution in Brahem's work (so far, eleven albums have been born of their association, all of them extremely well received by the international press and public on release); hIs discography is one of the loveliest in the ECM catalogue. To inaugurate this collaboration, Anouar made his first record in Oslo – Barzakh – that same year, together with two outstanding Tunisian musicians, Béchir Selmi and Lassaad Hosni, with whom he had already established a close artistic relationship. Considered by the German magazine Stereo as “a major musical event”, this record not only allowed Anouar Brahem to reach a larger international audience, it also guaranteed his status as “an exceptional musician and improviser”.

The following year, the heart of Conte de l’Incroyable Amour was improvisation. Recorded in 1991, its tone was quite different, due notably to the remarkable presence of Barbarose Erköse, whose clarinet displayed its expressive powers, and the Sufi inspiration of the ney played by Kudsi Erguner. According to the French paper Le Monde, "The album unfurls around the poetic talent of Anouar Brahem’s lute. One follows him with delight, around subtle arrangements of melody, through silences in musical phrases, and across the unspoken into oriental paths lit by the poetry of delicate beats." The same paper selected Conte de l’Incroyable Amour as one of 1992's best releases. That same year, he was solicited to help conceive and take an active part in the creation of the Centre for Arab and Mediterranean Music at the palace of Baron d’Erlanger in Sidi Bou Saïd.

In November 1993, he fulfilled a dream that had long been dear to him: that of paying a worthy tribute to his master Ali Sriti who, for the occasion, agreed to return to the stage after an absence of nearly thirty years… Brahem set up Awdet Tarab, a concert of traditional instrumental and vocal music, at the Erlanger Palace. The Tunisian public would retain an indelible memory of those duets played by master and pupil, accompanied by the voice of Sonia M’barek.

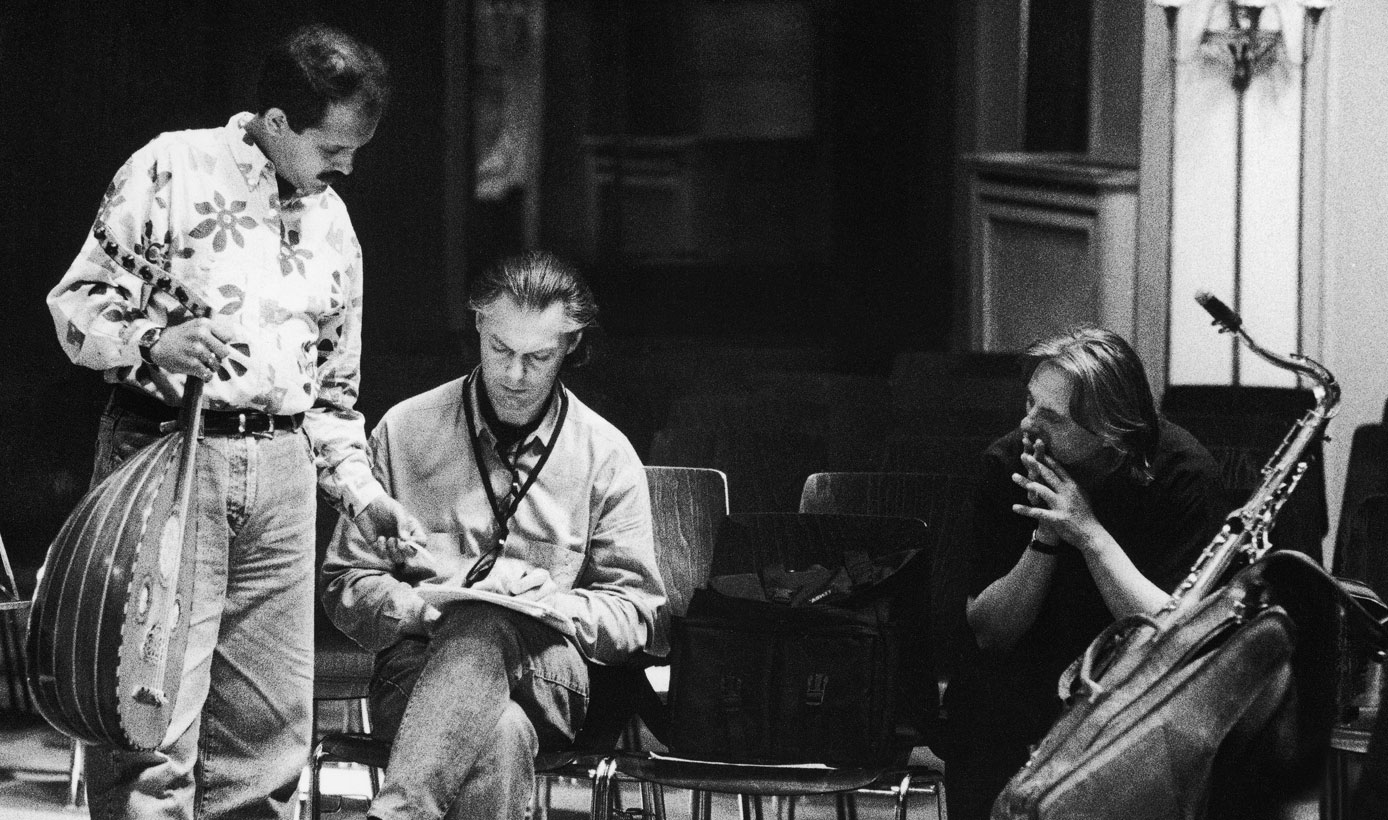

In 1994 he recorded Madar with Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek, and the master of the tabla Shaukat Hussain, from Pakistan. The story of this record is simply told: Jan Garbarek was impressed by Brahem’s first two albums, and had expressed a desire to work with him. Brahem had admired Garbarek for years, and shared the same wish. So their encounter happened quite naturally, warmly encouraged by Manfred Eicher: Brahem and Garbarek were united in a common quest, the search for a universal tradition. Madar was a strong statement on how to achieve the mingling of traditions without harming the essence of each.

Parallel to his personal work, Anouar Brahem pursued occasional collaborations, notably composing original scores for many films and plays, among them Sabots en Or and Bezness by Nouri Bouzid; Ferid Boughedir’s Halfaouine; Moufida Tlatli’s Les Silences du Palais and La Saison des Hommes; Iachou Shakespeare and Wannas El Kloub by Mohamed Driss; and El Amel, Borj El Hammam and Bosten Jamalek by the Phou Theatre.

With Khomsa in 1995, his fourth album for ECM, Brahem returned to some of the pieces he had always dreamed of performing, by offering inspired versions, free, airy and purely musical, in a manner "freed from the chains of images," as he put it. He assembled an eclectic formation to perform this music, including Richard Galliano (accordion), Palle Danielsson (double-bass), Jon Christensen (drums), François Couturier (piano), Jean-Marc Larché (saxophone) and Béchir Selmi (violin). The sextet put together by the composer was constantly divided into solos, duos and trios, "hence the dominant and delicious impression of being on a motionless voyage full of secret passages, novel tones, suspended endings," observed critic Alex Dutilh on the French radio-station France Musique. As for the British daily The Guardian, it declared “Khomsa is one of the great records of the year. Brahem is at the forefront of jazz because he is far beyond it." The first performance of Khomsa was given at the opening of the CIté de la musique in Paris in January 1995.

Three years later Anouar Brahem was back in the studios. He picked up where he had left off with Madar, passionately exploring the orchestral form of the trio much further, but this time in a context that was wide open to the infinite variety of the “worlds” of jazz. Brahem was flanked by two monumental musicians, both of them stalwarts of the ECM label for the last thirty years: saxophonist John Surman and double-bass player Dave Holland. They were the heralds of British free music in the late 60’s, and both have since continued in their own universe with great coherence, individualism and artistic perfection. With infinite delicacy, Anouar Brahem exposed the refined poetry of his instrument to the “risk” of improvisational concepts far removed from his own universe. The result was in keeping with the challenge: the album Thimar was an outstanding success, a meditative and supremely musical work permeated with intense poetry, where each piece was played in a contemplative atmosphere of extreme concentration, as if in a waking dream. On this record, without deviating from his personal aesthetic, Anouar Brahem explored the “mysteries of jazz” to an extent he had never reached before. In Germany, Thimar received the “Preis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik", an award which was followed by “Best Jazz Album of the Year” in the British magazine Jazz Wise.

Astrakan Café, his sixth album in ten years for ECM, was recorded this time in St. Gerold in Austria. for release in September 2000. To the inattentive listener it appeared to be, if not a work of transition, then at least an introspective pause in Anouar Brahem’s career. This would be a misreading of this music of maturity, for although the oud player undoubtedly revisited the Oriental and Mediterranean roots of his universe, he did so, undeniably, with the benefit of the wealth of imaginary aesthetic journeys contained in his preceding albums. Playing once again with his two most faithful partners – the clarinettist of Romany origin Barbaros Erköse, and Lassaad Hosni, the Tunisian percussionist – Brahem drifted away on a wonderfully intimate, eminently personal line, celebrating the syncretic spirit of Arab music while enhancing the approach to improvisation and collective sound which had been a feature of his two great, all-embracing works Madar and Thimar.

2002 undeniably marked a turning-point in the career of Anouar Brahem: his album Le Pas du Chat Noir was a totally atypical, extremely personal and quite ambitious work, not only in its aesthetic choices but also in its risk-taking orchestration, which caused a sensation while considerably renewing the components of Brahem's poetic universe.

The album was another trio recording, recorded in Zurich, but this time Brahem was accompanied by an old accomplice, pianist François Couturier, and, even more surprisingly, by the accordionist Jean-Louis Matinier. Anouar Brahem produced an extremely refined work of contemplative music whose richness of timbre – especially its miraculous, formal balance – referred listeners as much to the elegiac impressionism of French music from the beginning of the 20th century as to the meditative, sensualist traditions present in Arab music. In The New York Times, Adam Shatz echoed the general enthusiasm of the international media in an article where he stated, "If you consider that each orchestra collectively projects in its music a singular manner of being in the world, then the trio of Anouar Brahem, at once a jazz ensemble, a chamber orchestra and a traditional group, evokes a kind of 21st century Andalusia, where Arab and European sensibilities will have fused together so intimately that no frontier can any longer exist between them. All that might seem Utopian, but the beauty of this project is indisputable." The release of the record was followed by a long tour on both sides of the Atlantic, during which the group gained enormously in collective cohesion, while Anouar, every night, left a little more freedom to his companions in performing the repertoire.

In 2005, for the first time in his career, Anouar Brahem decided to take the same group into the studios in Lugano, Switzerland, for a second recording. Following an aesthetic line similar to Le Pas du Chat Noir – and perhaps delving further into the expressive outline by founding its essential discourse on nuances of timbre and increasingly sophisticated orchestral dynamics – the album Le Voyage de Sahar diffused its hypnotic poetry in subliminal fashion, with a repertoire of new compositions filled with emotions, lyricism and elegance, accompanied by a reprise of three of the composer's most famous pieces – ‘Vague’, ‘E la nave va’ and ‘Halfaouine’ — which became totally transfigured. It was a work of maturity, and it earned the musician an Edison Award in The Netherlands while providing the group with material to take on a new tour in Europe. It was a triumph.

The following year (2006), Anouar directed and coproduced his first documentary film, entitled “Mots d'après la Guerre”. It was a strong work of political commitment, set in Lebanon and articulated around interviews with Lebanese artists and intellectuals just after the cease-fire introduced that summer in the war between Israel and the Hezbollah. The film was selected for the 2007 Locarno Film Festival and met with great critical esteem. Brahem's increasing personal commitment to the world of films opened doors for him: in 2010 he was appointed to the Jury for the official feature-film selection shown at the Carthage Festival in Tunis.

That year, in a break with the "chamber-music" aesthetic of his two previous albums, Anouar Brahem released The Astounding Eyes of Rita, a record which proposed other bridges, other types of balance between modernism and the Arab tradition: it renewed with the tone of some of his previous works, like Barzakh and Conte de l’Incroyable Amour. Fronting a new group whose instrumentation was decidedly hybrid – a carpet of percussion laid down by Khaled Yassine, the misty bass clarinet of German reed-player Klaus Gesing, and the supple electric bass of Björn Meyer from Sweden –, Anouar Brahem, as if playing his oud in zero gravity, invented a fleecy, dreamlike universe which derived its poetic refinement and immensely dilated sense of space as much from Scandinavian jazz as from Oriental meditative traditions. Dedicated to the great Palestinian writer Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008), this magnificent intimist journey into the heart of sound marked a new phase in the constantly renewed marriage of Arab music and Western traditions to which Brahem tirelessly continues to devote himself. The Astounding Eyes of Rita, recorded in Udine (Italy), went on to receive one of Germany's most prestigious awards, the 2010 "Echo Deutscher Musikpreis" which, like the American Grammy Award, is attributed every year to the greatest national and international artists.

On December 9th 2009, Anouar Brahem gave his new quartet's first Parisian concert in the Salle Pleyel. Writing in La Pensée de Midi, critic Hugues Blondet was very enthusiastic in his review: “Pleyel, December 2009… The concert by Tunisian artist Anouar Brahem has just ended with a standing ovation, a rarity in this legendary venue… Three encores and the whole audience on their feet, overjoyed with happiness of a rare intensity”. Following this triumphant success, Anouar Brahem was decorated Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres by the French Minister for Culture and Communication, Frédéric Mitterrand.

In 2011 Tunisia was in revolt as it set out on the fiery and difficult path of emancipation. It was the beginning of the Arab Spring. Anouar Brahem “…profoundly marked by what has happened” was named a Life Member of the Beit El Hikma, Tunisian Academy for Science, Literature and the Arts. Then in 2014, he finally broke his silence after five years without any new release, and published Souvenance, an ambitious work mixing hypnotic and austere moments with great dramatic intensity. It is a work that can be interpreted as a personal, off-beat and meditative response to the political events that had so dramatically altered his homeland. The album, recorded in Lugano with the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana and blending the melodic enchantments of Anouar Brahem's oud, combined with the solo contributions of the members of his brand-new quartet – François Couturier on piano, Björn Meyer on electric bass and Klaus Gesing on bass clarinet – plunges us into the drapes of sound furnished by arrangements fora string-ensemble which are at once sumptuous and minimalist, resulting in music which has become even more refined in its melodic lines and orchestral textures, revealing both contemplation and narrative subtleties in developments whose inspiration shows great purity. In All About Jazz, John Kelman wrote, “In the end, this is what Souvenance really represents: a spiritual tale that explores the depths of feeling and the limits of the human condition.” This album has dared to bring a political obsession into the intimacy of music and individual reactions; it produced both unusually strong feelings and the desire for some serious thinking in those who heard it. It was given its first performance with the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra at the Carthage Festival’s 50th anniversary celebrations, where at least 7,500 people were ready to give this demanding music a standing ovation at the end of the concert.

In 2017, Anouar Brahem continued his universalist quest for harmony when he signed Blue Maqams, a new album recorded in New York and axed entirely around his deep love of jazz. As though taking up things where he had left them 20 years before with the album Thimar, already recorded with the British double-bass player Dave Holland and his compatriot John Surman, Brahem set up another small group where, this time, he added new ingredients to the happy reunion that was to come with Blue Maqams: Django Bates and the sheer joy and refinement of his harmonics on piano and the subtle rhythms of the legendary Jack DeJohnette on drums. Starting from original compositions blending great melodic sophistication with some deliberately simple formal structures, Brahem worked simultaneously on the finesse of timbre, the delicacy of the dynamics and the balance between instruments; the rich contributions arising from the continual interaction between these great improvisers highlighted the force of his personal poetics, clearly wholly integrated into his profoundly humanist musical vision. In his review of the CD for Jazz Magazine, Stéphane Ollivier has this to say: “Anouar Brahem, for his part, has never seemed so much master of his idiom, constantly finding as he does, the right balance between sensuality and abstraction. A total success.”

Blue Maqams was given its first public performance in July 2017 at Hammamet, where Nasheet Waits took the place of Jack de Johnette on drums. In April 2018, a few months after the date of release, the original quartet began a European tour, appearing in such prestigious concert halls as the Paris Philharmonie, as well as the one in Hamburg and that in Munich.

Deeply permeated with his Arab music legacy, yet also resolutely modern in his tastes and aesthetic orientations, Anouar Brahem is the very definition of “an artist of his time“, in other words, a musician turned towards the future and open to the great mutations of the world. This is no doubt the reason why he has no fear of "culture-shock". Better than that, Brahem has always delighted in provoking encounters with musicians of different horizons: Jan Garbarek, Richard Galliano, Dave Holland and John Surman of course, but also Manu Dibango, Manu Katché, Taralagati, Fareed Haque, Pierre Favre — all of them musicians who have at one time or another crossed paths with this adventurer in the world of Arab music. From every one of these encounters, Anouar Brahem has drawn the means to renew his universe while preserving his own identity. When asked about his inspiration, Anouar freely evokes the image of a tree which, "while rising above the ground and taking up more space, continues to develop and dig its roots deeper into the ground", an image which quite obviously has references to Tunis, his native city, a multi-faceted city rooted in its Arab-Muslim culture and nourished on its African and Mediterranean influences: a solar universe, as it were, one whose traces are always present in the work of this artist. Anouar Brahem believes that a tradition which is incapable of change and adaptation is doomed to die, which is why he has never hesitated to take up a challenge and open his music to new forms of expression. "He is so calm, so supreme that it would seem," wrote Wolfgang Sandner in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, "that the man from Tunisia has gone much further than many jazz musicians so busily seeking out new music." There is no better way to put it.