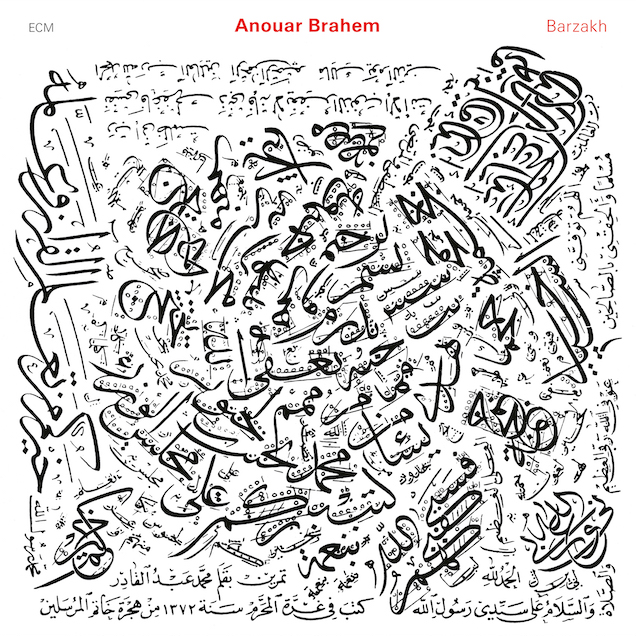

Anouar Brahem

Anouar Brahem, oud

Bechir Selmi, violin

Lassaad Hosni, percussion

Tracks

Raf Raf

Barzakh

Sadir

Ronda

Hou

Sarandib

Souga

Parfum de Gitane

Bou Naouara

Kerkenah

La Nuit des Yeux

Le Belvédère Assiégé

Qaf

Press reaction

"Marvelous, passionant [...] "Barzakh", the subtle intensity and authentencity of these timeless works."

Mittelbayerische Zeitung

Armin Maus

"[...] One of the major events of musical editions during the past few months, is a witness to the mastery of Arab musicians in the art of improvisation, which can serve as a model for jazz musicians, even coming after Coltrane."

Stereo

Karl Lippegaus

"[Barzakh] A real intercultural confrontation extreme virtuosity [...] he breathes through his lute from the depths of his body [...]"

Die Weltwoche

Peter Ruedi

"Musique méditative en nuances délicates [...] syncopes minimalistes et sobriété des ornementations, très beau."

Télérama

Eliane Azoulay

"Splendeur [...] La vénération que porte Anouar Brahem au FACING YOU de Keith Jarret ne semble en effet pas l’avoir arraché à sa tradition. S’il la fait évoluer, c’est, semble-t-il, en toute dévotion [...] jeu très introspectif."

Le Monde de la Musique

Frank Bergerot

"Les disques de musiciens exceptionnels, comme L . Shankar ou ici Anouar Brahem, à ce point maîtres de leurs instruments, le oud en l'occurrence, qu’ils dépassent les fondements de la tradition et s’élancent vers une culture hybride, que l’on peut présenter comme la modernité de la tradition."

Jazz Hot

Jean Paul Martin

"Barzakh nous a promené dans les lacis inextricables de la volupté musicale, un voyage intemporel où le respect de la tradition et les libertés d’improvisation créaient un feeling inégalable."

Le Temps

Hamadi Abassi

Accolades

6★ Epochal, "Mittelbayerische Zeitung" (Germany)

Liner note

One of the ironies of the current vogue for so-called world musics is that the adventurous listener often finds himself championing forms exotic to his ear which are, in their true context, fundamentally conservative. To be a traditional musician, wholeheartedly, is to be inflexible, resistant to change – and music that does not change hardens, calcifies, dies inside.

Anouar Brahem, a 33 year old and virtuoso (I don’t use the term casually) who holds the title Director of the Musical Ensemble of the City of Tunis, is acutely aware of this. Of his country’s players he laments, “we’ve lost much of the traditional instinctive interaction inherent in small groups of improvising musicians”. He fights against the malaise by refusing to limit himself to the exclusively Tunisian, however that might be defined, asking himself how many other idioms his branch of Arab music can move towards without compromising its integrity. He claims, for example, the right to examine “all the things left in my country by the colonialists, the occupiers”, thereby giving himself access to the musics of Spain, Turkey, Morocco, France and more; since the Roman occupation of the 2nd century B.C., Tunisia has changed hands constantly. Brahem’s partner on three of Barzakh’s tracks (including the crucial title piece), violinist Bechir Selmi, says: “Anouar is playing a music without borders... and that’s as it should be. Music cannot be contained within national boundaries.”

Anouar Brahem, a modern musician with profound for and knowledge of Arab classical music, is disinclined to be caged by its history.

He began playing the oud at 11, going on to receive a Diploma in Arab Music at the Tunis Conservatory and taking additional studies with oud master Ali Srithi, who now insists that “Anouar Brahem is the best lutenist in Tunisia. He has the touch and the feel. Only he knows the secret.” This view is not yet unanimously endorsed by other Tunisian musicians, some of whom view his innovations with suspicion. On the other hand, he has a growing following among the more progressive players. Bechir Selmi takes a special pleasure in the fact that Brahem has established the validity of an instrumental music in Tunisia. “With Anouar, a musician always feels he has more freedom than if he has to restrict himself to working around a singer.” Throughout the Islamic world, the singer and the song have held sway for centuries, even in such countries as Iran where an independent instrumental tradition has existed (albeit forced underground often enough).

Beyond the traditional field – to which he always returns for sustenance – Brahem has composed for ballet, theatre, and film, and mounted a number of large-scale “spectacles” in Tunisia, each conceived as a theatrical totality, with choice of venue, lighting and costumes interconnected with the music, the entire event awakening, by the musicians’ account, a “sense of ritual”. Such work led to his receiving Tunisia’s Grand Prix National de la Musique; he is the youngest artist to have received this award.

He has also embarked on many collaborations with musicians from other countries and cultures, including Renaissance lutenists, classical guitarists, flamenco players, sitarists. His resumé includes performances with Cameroon saxophonist Manu Dibango and Chicagoan-Chilean-Pakistani jazz guitarist Fareed Haque.

Although three self-produced cassettes were issued in his homeland, Barzakh is Anouar Brahem’s first album proper. It is almost impossible to buy records in Tunisia, let alone make them, and Brahem’s broad musical knowledge is attributable to his travels. He has toured in Algeria, Morocco, Spain, France, Italy, Yugoslavia, the USA and Canada and, for three years in the early 80s, was living in Paris, the city hailed by many as the crucible of the world’s folk resources on account of its large and extremely varied immigrant population.

It was while in Paris that he heard Keith Jarrett’s Facing You, an album that excited him greatly. Jarrett, he says, “often sounds extremely Andalusian when improvising on modes”. Further discographical investigations made an ECM aficionado out of him and by the time he reached Oslo for his own session he was exceptionally well-informed about the company’s history, directions, and production policy. Listening to the just-mixed final version of Gavin Bryars’s After The Requiem one evening at Rainbow, Anouar Brahem responded with a perspicacity one wouldn’t expect of many western musicians.

His ECM debut was first projected as a solo album, the lutenist opting to add violinist Bechir Selmi and percussionist Lassaad Hosni to the session to colour specific pieces. Though the musicians have played with each other in various contexts for years, they had never before worked in trio as they do on Parfum de Gitane and Kerkenah.

They are three very different characters. The trim, dapper Brahem, a strong-minded conceptualist, is very definitely the team leader. Selmi is an inspired working musician, open- minded, glad of a challenge, ready to play on any premise. It’s tempting, but too limiting, to think of him as an Arab Grappelli to Anouar’s Django, although Parfum de Gitane certainly suggests a Hot Club de Tunis. Hosni’s a good-natured, enthusiastic back-up man – it’s no surprise to learn that he plays a lot of parties and weddings back home – a gentle giant of a drummer, where Brahem and Selmi are slight of build.

As a child Bechir Selmi played the nay, the Arab flute, switching to violin at 15. At the Tunis conservatory, he studied both Arab music and Western classical and contemporary music, the latter under Czech and Bulgarian teachers – hence the intimation of a Janacek-Bartok Slovakian folk strain in his playing. But he is proud that the violin has its origins in Arab music (the art of bowing, in fact, was first established in the Islamic empire about 1000 years ago) and has recently begun to teach Near Eastern approaches to the instrument. Selmi is in the full-time employ of Tunisian television station RTT and plays constantly on its music programmes. “I am chained to my work”, he jokes. He is keen to acknowledge the pioneering work of three older Tunisian violinists who have influenced him greatly: Ridha Kalai, Naceur Zguonde and Belguacem Amaer, all now in their sixties. In 1987, Selmi joined the Musical Ensemble Of Tunis and, subsequently, has participated in all of Brahem’s Tunisian concerts.

Selmi has toured the Gulf countries playing both ancient and modern Arab music and says he experienced a personal breakthrough in 1988 while playing at the Opera in Cairo to an audience of musicians. “I gave them everything I had and I didn’t know what I gave them. I lost myself completely in the music, forgot the people in front of me, forgot my life. It was only afterwards I could piece together what I’d done.”

This intense commitment to the music’s flow is conveyed in Barzakh. The name, Brahem explains, refers to “the place of rest and tranquility where the soul goes before resurrection. It is an isthmus or transition.” Brahem says that for him Barzakh is “the album’s most important piece”. It was developed spontaneously in the studio in response to a production request for a slowly-unfolding legato performance to counterbalance the speeding rush of dazzling pieces like Raf Raf and Sarandib. It’s a question of emotion as opposed to adrenaline. There’s a place for both of course.

Percussionist Lassaad Hosni, in contrast to his well-schooled colleagues, is self-taught. Like drummers everywhere he beat the walls and the table as a child. At 14, he started playing darbouka, the clay goblet-drum capped with fish-skin for fast, snappy action. At 16 he was „making money with it.” It’s still his favourite instrument. Nonetheless at 17 he began to look at the Arab frame drum called the bendir and had to allow that, yes, despite its deeper, more ponderous sound that instrument had a lot of expressive potential, too. Hosni plays bendir on Parfum de Gitane and Kerkenah, darbouka on his two solo pieces Souga and Bou Naouara. The titles of the solos refer to the respective primary rhythms employed. Souga also includes a stambali rhythm, “the rhythm of the black Tunisians”, according to Hosni, while Bou Naouara which means literally “father of the flower”, reflects upon a chain of rhythms including the mramba, the tounsi, and the Algerian goubahi. Lassaad Hosni claims to be the only Tunisian darbouka player taking extended solos. His criteria for excellence? “When I play, I ask myself: Does it sound sweet?”

Lassaad Hosni first worked with Anouar Brahem in 1980. He is, additionally, a member of the Tunisian Folklore Group, which has toured widely under the auspices of the Tunisian Ministry of Culture, and has worked extensively with dancers and singers. I asked if he had any favourites amongst the vocalists he’s worked with and he wrote some names in my notebook. Half an hour later, he crossed the list out. All the other singers would be jealous, he explained. Better I mention just a couple of important dancers, Selwa Mohamed and Kawthar Cherif, and leave it at that.

In the cross-cultural zone, Hosni recently found himself working alongside Omar Hakim on a recording date with Theresa de Sio. The Neapolitan singer, having decided to cover one of Anouar Brahem’s tunes (”a piece almost like a Tunisian reggae”) brought the composer and his accompanist to the studio to participate ... but that’s a long way from the matter at hand.

With the exception of Kerkenah (the title alludes to the Tunisian island of the same name), recorded on the first, somewhat overexcited day of the Oslo session, all of Barzakh derives from a single day’s work. Brahem, marshalling all his resources, spun out solo pieces of a jewelled brilliance. Almost everything he played on Day Two merited inclusion on the record.

At his best, Brahem reveals exceptional clarity of execution and sensitivity to colour even when moving at top speed. Listen to the delightful Sarandib (the ancient name of Sri Lanka in Arabic), which challenges the fingers like one of Paganini’s Capricci.

The short pieces Hou and Qaf began life as alternate takes of the same tune. “They’re like haikus”, Brahem said, and indeed they are, each snaring a mood in a single, gentle pass. Hou, Brahem explains, is a contraction of the word Houa used in liturgical chants, while Qaf is a mythical mountain in Arab legend.

”He wanders freely amongst the universes, all of which are one: those which he inhabits, and those which inhabit him” – so, rather grandly, writes critic B. Ben Milad of one of Brahem’s Tunisian concerts. Brahem may soon be wandering freely out of Tunis, feeling the need to move on again.

”It may be time for me to leave”, he says. “I’d like to explore more of the world, live in India for six months, meet and play with a broader range of musicians. It’s dangerous if you keep playing to the same audience. It’s really important that the music should change and grow.”

Steve Lake

(with thanks to Patrick Papania for his multi-lingual translations)