Anouar Brahem

Anouar Brahem, oud

Béchir Selmi, violon

Lassâad Hosni, percussion

Pistes

Raf Raf

Barzakh

Sadir

Ronda

Hou

Sarandib

Souga

Parfum de Gitane

Bou Naouara

Kerkenah

La Nuit des Yeux

Le Belvédère Assiégé

Qaf

Réaction presse

"Musique méditative en nuances délicates [...] syncopes minimalistes et sobriété des ornementations, très beau."

Télérama

Eliane Azoulay

"Splendeur [...] La vénération que porte Anouar Brahem au FACING YOU de Keith Jarret ne semble en effet pas l’avoir arraché à sa tradition. S’il la fait évoluer, c’est, semble-t-il, en toute dévotion [...] jeu très introspectif."

Le Monde de la Musique

Frank Bergerot

"Les disques de musiciens exceptionnels, comme L . Shankar ou ici Anouar Brahem, à ce point maîtres de leurs instruments, le oud en l'occurrence, qu’ils dépassent les fondements de la tradition et s’élancent vers une culture hybride, que l’on peut présenter comme la modernité de la tradition."

Jazz Hot

Jean Paul Martin

"Barzakh nous a promené dans les lacis inextricables de la volupté musicale, un voyage intemporel où le respect de la tradition et les libertés d’improvisation créaient un feeling inégalable."

Le Temps

Hamadi Abassi

"Marvelous, passionant [...] "Barzakh", the subtle intensity and authentencity of these timeless works."

Mittelbayerische Zeitung

Armin Maus

"[...] One of the major events of musical editions during the past few months, is a witness to the mastery of Arab musicians in the art of improvisation, which can serve as a model for jazz musicians, even coming after Coltrane."

Stereo

Karl Lippegaus

"[Barzakh] A real intercultural confrontation extreme virtuosity [...] he breathes through his lute from the depths of his body [...]"

Die Weltwoche

Peter Ruedi

Distinctions

6★ Epochal (Fera date), "Mittelbayerische Zeitung" (Allemagne)

Note de livret

L’une des ironies de la vogue actuelle pour les musiques dites "du monde" est que l’auditeur aventureux se retrouve souvent à défendre des formes exotiques à son oreille mais qui, dans leur véritable contexte, sont fondamentalement conservatrices. Être un musicien traditionnel, au sens plein du terme, c’est être inflexible, résistant au changement – et une musique qui ne change pas se fige, se calcifie, meurt à l’intérieur.

Anouar Brahem, 33 ans, virtuose (je n’emploie pas ce terme à la légère) et directeur de l’Ensemble Musical de la Ville de Tunis, en est pleinement conscient. Il déplore, à propos des musiciens de son pays : "Nous avons perdu une grande part de l’interaction instinctive traditionnelle qui animait les petits groupes de musiciens improvisateurs." Il combat ce mal en refusant de se limiter à l’exclusivement tunisien, quelle que soit la définition qu’on lui donnerait, se demandant jusqu’où son idiome musical arabe peut se tourner vers d’autres horizons sans perdre son intégrité. Il revendique, par exemple, le droit d’examiner "tout ce que mon pays a conservé des colonialistes, des occupants", ce qui lui ouvre l’accès aux musiques d’Espagne, de Turquie, du Maroc, de France et bien d’autres encore ; depuis l’occupation romaine au IIe siècle avant J.-C., la Tunisie est passée de main en main. Le violoniste Bechir Selmi, son partenaire sur trois des morceaux de Barzakh (dont la pièce-titre essentielle), déclare : "Anouar joue une musique sans frontières… et c’est ainsi que cela doit être. La musique ne peut pas être contenue à l’intérieur de frontières nationales."

Anouar Brahem, musicien moderne doté d’un savoir et d’une connaissance profonde de la musique arabe classique, n’a guère l’intention de se laisser enfermer par l’histoire.

Il a commencé l’oud à l’âge de 11 ans, a obtenu un diplôme de musique arabe au Conservatoire de Tunis, puis a poursuivi sa formation auprès du maître de l’oud Ali Sriti, qui affirme aujourd’hui : "Anouar Brahem est le meilleur luthiste de Tunisie. Il a le toucher et le ressenti. Lui seul connaît le secret". Ce jugement n’est pas encore unanimement partagé par les musiciens tunisiens, dont certains regardent ses innovations avec méfiance. Mais il gagne de plus en plus de partisans parmi les instrumentistes progressistes. Bechir Selmi apprécie tout particulièrement que Brahem ait affirmé la validité d’une musique purement instrumentale en Tunisie : "Avec Anouar, un musicien se sent toujours plus libre que lorsqu’il doit se cantonner à accompagner un chanteur." Dans le monde islamique, le chanteur et la chanson dominent depuis des siècles, même dans des pays comme l’Iran où a subsisté – souvent contrainte à l’ombre – une tradition instrumentale indépendante.

Au-delà du champ traditionnel – auquel il revient toujours s’abreuver – Brahem a composé pour le ballet, le théâtre et le cinéma, et a conçu en Tunisie plusieurs grands "spectacles" pensés comme des ensembles théâtraux : choix du lieu, lumières et costumes étaient conçus en relation avec la musique, l’ensemble éveillant, selon les musiciens, un "sentiment de rituel". Ce travail lui a valu le Grand Prix National de la Musique en Tunisie ; il est le plus jeune artiste à l’avoir reçu.

Il a également multiplié les collaborations avec des musiciens d’autres pays et d’autres cultures : luthistes de la Renaissance, guitaristes classiques, flamencos, sitaristes. Son parcours comprend des prestations avec le saxophoniste camerounais Manu Dibango et le guitariste de jazz chicagoan-chilien-pakistanais Fareed Haque.

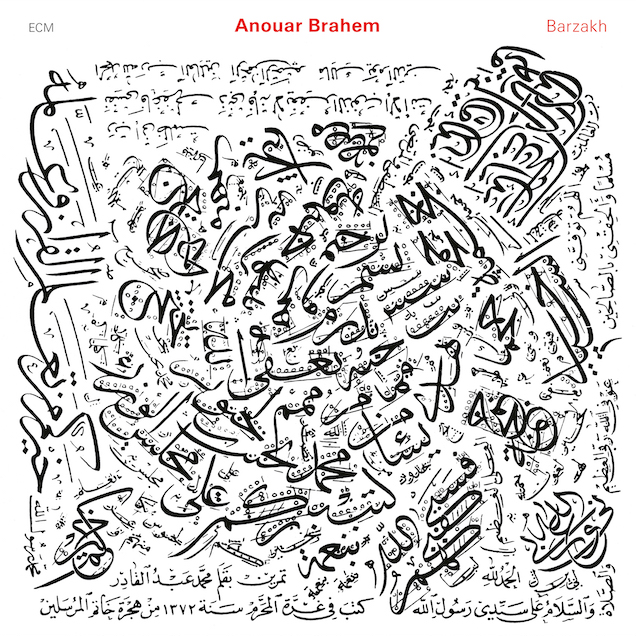

Bien que trois cassettes autoproduites soient parues dans son pays, Barzakh est le premier véritable album d’Anouar Brahem. En Tunisie, acheter un disque – a fortiori en produire un – relève presque de l’impossible. Sa vaste connaissance musicale, il la doit à ses voyages. Il a joué en Algérie, au Maroc, en Espagne, en France, en Italie, en Yougoslavie, aux États-Unis et au Canada et, durant trois ans au début des années 1980, il a vécu à Paris, ville que beaucoup considèrent comme le creuset des musiques du monde en raison de sa population immigrée, vaste et diverse.

C’est à Paris qu’il découvrit Facing You de Keith Jarrett, un album qui l’a profondément marqué. Jarrett, dit-il, "sonne souvent extrêmement andalou lorsqu’il improvise sur des modes." Ses explorations discographiques l’ont rapidement fait devenir un aficionado d’ECM et, lorsqu’il est arrivé à Oslo pour sa propre session, il était déjà remarquablement informé sur l’histoire, l’orientation et la politique de production du label. En écoutant un soir, au Rainbow Studio, la version tout juste mixée de After The Requiem de Gavin Bryars, Anouar Brahem a réagi avec une perspicacité qu’on ne s’attendrait pas à trouver chez beaucoup de musiciens occidentaux.

Son premier projet pour ECM devait être un album solo ; le luthiste a finalement choisi d’y associer le violoniste Bechir Selmi et le percussionniste Lassaad Hosni afin de colorer certaines pièces. Bien qu’ils se connaissent depuis longtemps et aient souvent joué ensemble dans divers contextes, ils n’avaient encore jamais travaillé en trio comme ils le font ici sur Parfum de Gitane et Kerkenah.

Ce sont trois personnalités très différentes. Brahem, mince et élégant, est un conceptuel au caractère affirmé, indiscutablement le meneur de l’équipe. Selmi est un musicien de métier inspiré, ouvert, avide de défis, prêt à jouer sur n’importe quel terrain. La tentation est grande, bien que trop réductrice, de le voir comme un Grappelli arabe face au Django d’Anouar – Parfum de Gitane évoque d’ailleurs fortement un « Hot Club de Tunis ». Hosni, bon vivant et enthousiaste, est un accompagnateur idéal – nul étonnement à apprendre qu’il joue beaucoup lors de fêtes et de mariages en Tunisie. Géant doux de la percussion, il contraste physiquement avec ses deux partenaires de plus frêle stature.

Dès l’enfance, Bechir Selmi jouait du nay, la flûte arabe, avant de passer au violon à 15 ans. Au conservatoire de Tunis, il a étudié à la fois la musique arabe et la musique classique et contemporaine occidentale, auprès notamment de professeurs tchèques et bulgares – d’où cette touche de folklore slovaque à la Janáček ou Bartók qui affleure parfois dans son jeu. Mais il est fier de rappeler que le violon plonge ses origines dans la musique arabe (l’art de l’archet, en fait, s’est établi pour la première fois dans l’empire islamique il y a environ mille ans) et il a récemment commencé à enseigner des approches proche-orientales de l’instrument. Employé à plein temps par la télévision tunisienne RTT, il y joue constamment dans des programmes musicaux. "Je suis enchaîné à mon travail", plaisante-t-il. Il tient à saluer l’œuvre pionnière de trois violonistes tunisiens plus âgés qui l’ont profondément influencé : Ridha Kalai, Naceur Zguonde et Belguacem Amaer, tous trois aujourd’hui sexagénaires. En 1987, Selmi a intégré l’Ensemble Musical de Tunis et a, depuis, participé à tous les concerts tunisiens de Brahem.

Il a aussi tourné dans les pays du Golfe, jouant aussi bien la musique arabe ancienne que moderne, et dit avoir connu une révélation personnelle en 1988, lorsqu’il se produisit à l’Opéra du Caire devant un auditoire de musiciens. "Je leur ai tout donné sans savoir ce que je donnais. Je me suis complètement perdu dans la musique, j’ai oublié le public, j’ai oublié ma vie. Ce n’est qu’après coup que j’ai pu reconstituer ce que j’avais fait."

Cette intensité, ce flux, se retrouvent dans Barzakh. Le titre, explique Brahem, désigne "le lieu de repos et de tranquillité où l’âme se rend avant la résurrection. C’est un isthme, une transition." Pour lui, Barzakh est "la pièce la plus importante de l’album". Elle s’est développée spontanément en studio, en réponse à une demande de production : offrir une performance legato, lente et progressive, pour contrebalancer la virtuosité effervescente de pièces éclatantes comme Raf Raf ou Sarandib. Il s’agit ici d’émotion plutôt que d’adrénaline. Il y a bien sûr une place pour les deux.

Le percussionniste Lassaad Hosni, à l’opposé de ses collègues passés par le conservatoire, est autodidacte. Comme tous les batteurs, il a commencé enfant en frappant murs et tables. À 14 ans, il s’est mis à la darbouka, tambour en terre cuite à peau de poisson, parfait pour les attaques rapides et claquantes. À 16 ans, il "gagnait déjà de l’argent avec". La darbouka reste son instrument de prédilection. Mais dès 17 ans, il s’est intéressé au bendir, grand tambour sur cadre, et a dû admettre que, malgré son timbre plus grave et plus ample, il recelait lui aussi un immense potentiel expressif. Hosni joue du bendir sur Parfum de Gitane et Kerkenah, et de la darbouka dans ses deux solos Souga et Bou Naouara. Ces titres renvoient aux rythmes principaux employés. Souga incorpore également un rythme stambali, "le rythme des Noirs tunisiens", selon Hosni, tandis que Bou Naouara ("père de la fleur") enchaîne différents cycles : mramba, tounsi, goubahi algérien. Hosni affirme être le seul joueur de darbouka en Tunisie à se lancer dans de longs solos. Son critère ? "Quand je joue, je me demande : est-ce que ça sonne doux ?"

Hosni a travaillé pour la première fois avec Brahem en 1980. Il est également membre du Groupe Folklorique Tunisien, qui a beaucoup tourné sous l’égide du ministère de la Culture, et a collaboré avec de nombreux danseurs et chanteurs. Lorsqu’on lui demande de citer ses chanteurs favoris, il note quelques noms… puis les raye une demi-heure plus tard : "Les autres seraient jaloux." Mieux vaut, dit-il, ne mentionner que deux danseuses importantes : Selwa Mohamed et Kawthar Cherif.

Dans le champ des échanges interculturels, Hosni s’est récemment retrouvé aux côtés d’Omar Hakim pour un enregistrement avec la chanteuse napolitaine Teresa De Sio. Celle-ci, ayant choisi de reprendre une pièce de Brahem ("un morceau presque comme un reggae tunisien"), avait invité le compositeur et son accompagnateur à participer à la séance… mais c’est déjà une autre histoire.

À l’exception de Kerkenah (allusion à l’île tunisienne du même nom), enregistrée le premier jour – un peu trop fébrile – de la session d’Oslo, l’ensemble de Barzakh provient d’une seule journée de travail. Brahem, mobilisant toutes ses ressources, a déployé en solo des pièces d’un éclat joaillier. Presque tout ce qu’il a joué ce deuxième jour méritait d’être retenu pour le disque.

À son meilleur, Brahem révèle une clarté d’exécution exceptionnelle et une sensibilité aux couleurs jusque dans la virtuosité la plus rapide. Écoutez le délicieux Sarandib (ancien nom arabe du Sri Lanka), qui met les doigts au défi comme un caprice de Paganini.

Les courtes pièces Hou et Qaf sont nées comme prises alternatives d’un même thème. "Elles sont comme des haïkus", dit Brahem – et en effet, chacune saisit une humeur d’un seul geste délicat. Hou, explique-t-il, est une contraction du mot Houa utilisé dans les chants liturgiques, tandis que Qaf désigne une montagne mythique des légendes arabes.

"Il erre librement parmi les univers, qui ne sont en réalité qu’un seul : ceux qu’il habite et ceux qui l’habitent" – écrit, un brin grandiloquent, le critique B. Ben Milad à propos d’un concert tunisien de Brahem. Et peut-être que bientôt Brahem lui-même quittera librement Tunis, ressentant à nouveau le besoin de partir.

"Il est peut-être temps pour moi de partir, dit-il. J’aimerais explorer davantage le monde, vivre six mois en Inde, rencontrer et jouer avec un éventail plus large de musiciens. C’est dangereux de jouer toujours devant le même public. Il est vraiment important que la musique change et grandisse."

Steve Lake

(avec tous nos remerciements à Patrick Papania pour ses traductions multilingues)