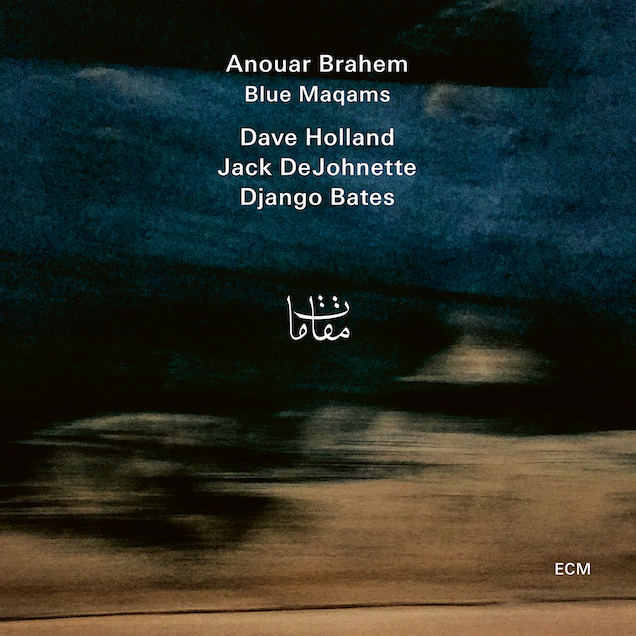

Anouar Brahem

Anouar Brahem, oud

Dave Holland, double bass

Jack DeJohnette, drums

Django Bates, piano

About

Recorded in New York’s Avatar Studios in May 2017 and produced by Manfred Eicher, Blue Maqams brings Tunisian oud master Anouar Brahem together with three brilliant improvisers. For Anouar Brahem and Dave Holland the album marks a reunion: they first collaborated 20 years ago on the very widely-acclaimed Thimar album. Brahem meets Jack DeJohnette for the first time here, but Holland and DeJohnette have been frequent musical partners over the last half-century beginning with ground-breaking work with Miles Davis – their collaborations are legendary. British pianist Django Bates also rises superbly to the challenge of Brahem’s compositions. And Anouar in turn is inspired to some of his most outgoing playing.

Tracks

Opening Day

La Nuit

Blue Maqams

Bahia

La Passante

Bom Dia Rio

Persepolis's Mirage

The Recovered Road to Al-Sham

Unexpected Outcom

Press reaction

"For his intriguing new quartet album, ‘Blue Maqams’, master oudist Anouar Brahem enlisted two fellow legends and a veteran player whose profile is on the rise. […] Not only did Brahem find the perfect collaborator in Bates, he assembled a program of all original compositions that showcases the pianist’s gorgeous touch, with some passages featuring solo piano, as well as duo sections that highlight subtle, intelligent conversations between oud and piano. […] The result is a program that features traditional music from Arab culture as well as more modern jazz elements. Each musician shines here."

Downbeat

Bobby Reed (Editor’s Pick)

"Blue Maqams has no need to pound or poke, finding tranquility in the pragmatic acoustic formula and unblemished technique evinced by the quartet. In these disturbing times, nothing better than listening to music that is congenial, peaceful, and deeply felt. Anouar Brahem delivers all that and more."

Jazz Trail

Filipe Freitas

"Blue Maqams will not only go down as one of the year's best ECM Records releases; it's a classic-in-the-making that should ultimately be considered one of the label's very best recordings in its nearly fifty-year history."

All About Jazz

John Kelman

"This glitzy lineup features his bass-playing soulmate Dave Holland, drums star Jack DeJohnette, and a wild card in the form of the UK’s Django Bates on piano. The result achieves a spellbinding balance between gently melodic Mediterranean song forms and the one-touch rhythmic elasticity and melodic ingenuity of the best jazz. The presence of Bates (producer Manfred Eicher’s idea, Brahem never having heard the English maverick before) is an inspiration, for his lyrical restraint, creative spaciousness, and diverse references. […] It’s a real meeting of hearts and minds."

The Guardian

John Fordham

"The album title signifies the union between the incredibly complex Arabic modal and harmonic system and the ‘blue’ so often evoked in jazz improvisation. Throughout, Brahem seamlessly combines the uncommon time signatures, sonic timbres, and whole-tone textures of Arabic music with the dynamic adventure of jazz improv. […] ‘Blue Maqams’ is lovely. It's a nearly perfect illustration of balance between cultural and musical inquiry, underscored by the confidence and near symbiotic communication of this gifted ensemble. This is an exceptional outing, even for an artist as accomplished and creative as Brahem."

All Music

Thom Jurek

"The whole session has a tremulous, simmering intensity. The title refers to Arabic modes, the richness of which is grist to the mill of an imaginative composer-improviser such as Brahem, and he draws on them extensively, presenting compositions in which curled, careening melody enhances the strong ensemble voice. However, in the moments when the group breaks down to leave him unaccompanied he excels by way of phrasing that is majestically doleful, conveying moods that are then heightened by gently brushed, mandolin-like yearnings of Bates’ right hand. For both the poise and restraint of the band as well as the beauty of the tonal palette and material this is a strong entry in Brahem’s discography."

Jazzwise

Kevin Le Gendre

"His most recent release, ‘Blue Maqams’, showcases his skills in a jazz context – the results are simply stunning. […] We're dealing with musicians who know how to extract every nuance and ounce of meaning from a note. […] As one would expect from a collection of such experienced and gifted musicians, the quality of performance is not only exemplary, it's awe-inspiring […] ‘Blue Maqams’ is a gem of an album featuring four incredibly gifted musicians. […] Anouar Brahem has composed nine amazing works and they are brought to life on this album with amazing skill and grace."

Qantara.de

Richard Marcus

"When I first heard Maqams, oddly enough ‘In a Silent Way’ came to mind, not so much for content, which couldn’t be more different, but in the way both albums wash over the listener, enveloping them in a specific environment, not unlike immersing oneself in a great ocean of spacious sounds, one that, like the sound of the surf, can be put on repeat without tiring of it. Each piece seems to flow inevitably and effortlessly into the next. And there is a connection between these two fine albums: they both have Dave Holland on bass. Holland is like a rock in both settings, laying down the groove and stating the time when necessary, floating when appropriate. DeJohnette, a powerhouse drummer, opts to sit in the background for the most part here, sometimes sitting out altogether, and only showing his formidable creativity and chops in a couple key places. Pianist Django Bates shows particular discipline in the way he interacts with Brahem’s passionate, sensual, yet understated oud. There is not a note that doesn’t belong- the interaction is a precise give and take, sometimes almost call and response, but the two never get in the way of one another. […] I can’t recommend this album highly enough. And I honestly can’t remember the last time I found something so inherently listenable that I just put it on repeat while hanging out at home. Yet putting one’s entire concentration on the music yields vast rewards. It is that good after all!"

Manafonistas

Brian Whistler

"From the very first moments – ‘Opening Days’ begins with a characteristically delicate, thoughtful solo introduction from the leader’s oud – the music is unmistakably Brahem’s; but within seconds you know this is also going to be something rather different. Joining the oud, first we have Dave Holland’s rich, thumping bass; then the crisp, light, swinging accompaniment of Jack DeJohnette on drums; and finally, a couple of minutes into the track, Django Bates’ piano makes its magical entrance, fittingly lyrical yet significantly ‘jazzier’."

Notes & Observations

Geoff Andrew

"So how does Brahem’s Arabic modal music background mesh with these jazz masters? Will one drown out the other or will they meet in the middle? Often Brahem begins tracks with solo oud and the players gradually come in (or, on ‘La Passente’, the track never ignites, but smoulders gently throughout). So no clash there. But the title track begins with drums and here Brahem’s oud functions like a guitar, beautifully intertwining with Bates’s piano until everything else drops away, then re-emerging to resolve the piece at the end. It is one of serveral places where the two forms show utmost respect and bring the best out of each other. […] this album works on several levels. Its jazz, exotic mood is unobtrusive and enjoyable as background, but start to go deeper and there is so much to explore in this musical meeting of worlds."

Church of England Newspaper

Derek Walker

"With a title that sums up its mix of complex but melodic Arabic modes and the so-called blue notes of jazz improvisation, this album by Tunisian oud master Anouar Brahem is part world fusion, part work of art. [….] These 10 improvisations see the maestro challenged by changes in tempo and exercises in swing, bossa nova and solo invention. But always, the oud is granted freedom to fly. Sublime."

Evening Standard

Jane Cornwell

"What is clear from this recording as a whole is that Anouar Brahem has a clear vision of what he is seeking to achieve and the musicians on board this project are of a sufficiently high caliber to deliver the goods with aplomb. An outstanding recording that easily fits into the best albums of the year category."

UK Vibe

Tim Stenhouse

"Oud-master Anouar Brahem's instantly intoxicating ‘Blue Maqams’ caps off a truly remarkable year for ECM Records. […] A maqam defines traditional Arab musical phrases, tones, notes and melodies but eschews control of rhythm, making all these blue maqams, these tightly composed universes, light years of inspiration and interpretation for Brahem's three daring cohorts, bassist Dave Holland, drummer Jack DeJohnette and the mischievous creativity of pianist Bates. They deliver non-stop."

All About Jazz

Mike Jurkovic

"The characteristics of Brahem’s native Tunisia are apparent in the ostinato rhythms, cyclical scales and horizontal organization. Underneath is a power that comes from the subtle individualism of the music. This is not a fusion, but a holistic synthesis of traditional North African musics, jazz and improvisation. […] Brahem’s improvising is relaxed, each note full of purpose. Credit the rhythm section for seamlessly following the 60-year-old leader. Everyone handles the pattern-based forms with an easy flow. No surprise with bassist Dave Holland, who has a monumental sound, and Jack DeJohnette’s trademark ticking cymbal sound is there, but in all other ways the drummer is so deeply submerged into the aesthetic that he sounds like an entirely different musician. […] This is a long album that’s constantly absorbing and affecting."

Downbeat

George Grella

"It’s seldom clear what’s traditional and what modern in Brahem’s music, because it constantly wanders between – and thereby dissolves – these reference points. It’s a sensibility he shares with the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, to whom he dedicated his 2009 album ‘The Astounding Eyes of Rita’. Like Darwish’s ‘lyric epic’, Brahem’s music suggests that there is nothing more modern than a tradition that has been given new life. An embrace of the new is also the road home for an improvisatory tradition that has drifted astray from its exploratory roots. (The title of one track, ‘The recovered road to al-Sham’, an allusion to Syria, suggests that innovation and freedom might heal other forms of exile.) The mood throughout ‘Blue Maqams’ is one of restless transformation and searching, as the music’s different elements combine to form a new alloy that floats free of its hybrid origins, but never forgets them."

London Review of Books

Adam Shatz

"This is a gently exquisite album, in which the finest and most innovative oud (lute) player in Tunisia is joined by three of the most skilful improvisers in the jazz world today […] There are passages where the subtle oud playing is echoed by thoughtful piano work, and others where the piano takes the lead, or a repeated bass line is used to underpin the oud and piano improvisation. It’s a thrilling meeting of master musicians."

Songlines

Robin Denselow

"For ‘Blue Maqams’, his tenth LP on the venerable ECM label, Tunisian oudist Anouar Brahem shifts away from the grand concepts that drove his previous album Souvenance, instead convening a jazz trio. And what an ensemble it is, too. Veteran British pianist Django Bates (Bill Bruford, Tim Berne) takes the chordal helm, with Jack DeJohnette and Dave Holland – perhaps the greatest living rhythm section in jazz – providing supple support. Melody rules here; Brahem’s ability to blend jazz changes with the Middle Eastern tonalities of his homeland gives each song a distinctive tone, accessible yet challenging. […] Masterfully performed and arranged, ‘Blue Maqams’ is a record of great beauty and fire."

Blurt

Michael Toland

"Blue Maqams, un album cousu de douceur et d’élégance, brillant de la sensibilité des musiciens épatants réunis par l’oudiste et compositeur tunisien […] Tout a parfaitement fonctionné. Le résultat enchante."

Le Monde

Patrick Labesse

"Il revient aujourd’hui à ses premières amours transversales en signant un disque magnifique entièrement animé par sa passion du jazz. Retrouvant pour l’occasion Dave Holland à la contrebasse, magistral de fluidité et de profondeur, Brahem prend le risque de réintroduire la batterie dans l’équilibre si fragile de son univers évanescent, confiant à Jack DeJohnette le soin d’adapter tambours et cymbales aux dynamiques subtiles de sa musique. Le résultat est un modèle de musicalité et de féérie sonore minimaliste. Convié également à la fête, le pianiste anglais Django Bates, dont on aurait pu douter a priori que sa personnalité volontiers décalée et extravagante convienne à ce genre de projet intimiste, est la grande et bonne surprise du disque. Transfigurant par la magie de son toucher les parties très écrites des compositions modales envoûtantes de Brahem, le pianiste fait par ailleurs preuve d’une inventivité et d’une inspiration constante, apportant à l’ensemble la richesse de ses harmonies et la vivacité de son phrasé. [...][Anouar Brahem] de son côté n’a jamais semblé aussi maître de son discours, trouvant constamment la bonne balance entre sensualité et abstraction. Une réussite totale."

Jazz Magazine

Stéphane Ollivier

"Un disque comme un bijou. Tout est ici affaire de profondeur et de pureté dans les lignes, de rigueur et de liberté dans l’exécution, d’élégance et de richesse dans les textures. Autour du oud de Brahem, on trouve un quartet premium (Holland, DeJohnette) qui navigue avec brio entre le jazz et le système modal de la musique arabe traditionnelle. Pure poésie."

Le Devoir

Guillaume Bourgault-Côté

"Ce nouvel album d'une dignité musicale absolue, d'une haute vertu d'inspiration, est l'un des meilleurs cette année."

Classica

Jean-Pierre Jackson

"Laissons le maître tunisien Anouar Brahem nous remettre sur le droit chemin avec son oud magique."

France inter

André Manoukian (La Matinale)

"[…] Sa musique riche d'intériorité n'a jamais été aussi sereine. Le travail minimaliste effectué sur les partitions et la sobriété des arrangements ont fait naître un album dépouillé et intemporel qui a la beauté du frisson. Aucune démonstration, aucune fioriture, il s'agit là d'aller à l'essentiel. Le son tout simplement magnifique et l'univers envoûtant d'Anouar Brahem portent celle, celui qui l'écoute en apesanteur vers une humanité où l'on se surprend à croire que tout est possible. Si l'oud est l'instrument du Tarab qui signifie l'émotion poétique et musicale, celui d'Anouar Brahem nous mène bien à l'extase."

Radio FIP

Cédric Lalanne

"La delicadeza es el pilar más fuerte de la música de Anouar Brahem [….] El sutil timbre de su laúd árabe requiere que los demás instrumentos que le acompañan sean igual de discretos. […] Pero la suavidad va más allá de su peculiar estilo, que mezcla tradición arábiga con jazz, y es también la esencia con la que entiende la música. Casi todo lo que se oye en el álbum, dice, fue concebido “en la magia de un momento de inspiración”, sin mucha planificación, pero sí con la sensibilidad despierta. Brahem no construye sus discos como obras integrales, sino que cada pieza es un universo particular que surge a partir de pequeñas ideas. (Delicacy is the strongest pillar of Anouar Brahem’s music […]. The subtle timbre of his Arab lute requires that the other instruments that accompany him are equally discrete. […] But the softness goes beyond his characteristic style, which mixes Arabian traditions and jazz, and is also the essence with which he understands music. Almost everything that is heard in this album, he says, was conceived “in the magic of a moment of inspiration”, without much planning, but with aroused sensibility. […] each piece is a particular universe that emerges from small ideas."

El País

Alejandro Mendoza Arriaga

"Zu seinem 60. Geburtstag hätte Anouar Brahem sich und uns kein schöneres Geschenk machen können als diese Session in New York vom Mai 2017. […] Wie Sterne am Himmel über der Media von Tunis leuchten die Klänge, die Brahem mit seinen drei Mitspielern erzeugt. Das vielbeschworene Thema Orient & Okzident bekommt eine neue Bedeutung durch die Art, wie sich hier ein Dialog zwischen Oud und Klavier entspinnt. […] Seit Anouar Brahems Erfolgsalbum ‚Le Pas du Chat Noir‘ (2002) dürfte ‚Blue Maqams‘ die Platte werden, die am meisten auch die Hörer ansprechen wird, die weder in der klassischen arabischen Musik noch im zeitgenössischen Jazz bewandert sind. Hier ist es zu hören – ‚the best of both worlds‘."

Stereo

Karl Lippegaus

"Ein leiser Schlagzeug-Rhythmus - und darüber die Instrumenten-Stimme von Anouar Brahem. Ein Blues sozusagen. Aus Tunesien. So beginnt das Titelstück dieser CD - und es ist repräsentativ. Anouar Brahem, einer der weltweit berühmtesten Spieler der arabischen Laute Oud, hat sich hier mit neuen Partnern zusammengetan. Es sind Schlagzeuger Jack DeJohnette, Bassist Dave Holland und Pianist Django Bates. Drei Weltstars des modernen Jazz. Brahem selbst betrachtet sich nicht als Jazz-Musiker, er vermeidet gängige Kategorien. Als Komponist und Improvisator hat er zwischen arabischen und westlichen Musiktraditionen einen eigenen Ton gefunden - und da ist es besonders spannend zu hören, wie er sich in diesem neuen Quartett bewegt. Er tut es auf scheinbar selbstverständliche Art. Und doch nicht so, als wolle er den Hörern einreden, die Oud sei in den Kellergewölben eines Jazzclubs großgeworden und habe bei Festivals wie Newport oder Montreux die Reifeprüfung abgelegt. Er findet auch hier wieder einen ganz eigenen Klang."

Bayrischer Rundfunk

Roland Spiegel

"Brahem vermählt den Maqam, Tonleitern aus der klassischen arabischen Kunstmusik, mit dem ‚Blue‘ des jazz. Auf seinem Album lassen sich die Musiker tatsächlich aufeinander ein: Die Jazzmusiker nehmen in den Stücken "Opening Day" und "La Nuit" den behutsamen Tonfall der Oud auf, untermalen die Töne sublim, mit viel Atem und Ruhe. […] Im Titelstück ‚Blue Maqams‘ wiederum nähert sich Brahem dem Jazz an. Es herrscht eine ganz andere Atmosphäre: Zum arabischen Geist tritt dezent eine Jazzharmonik dazu. So bringt dieses Album einen Dialog sozusagen auf dem west-arabischen Diwan: Es lässt sich als vielmehr hören als nur ein Stück Worldmusic – ein Etikett, das Brahem ohnehin verabscheut."

Tagesanzeiger

Christoph Merki

"Maqam, das ist der Modus in klassischer arabischer und türkischer Musik. Und diese ‚Blue Maqams‘, die sind Brahems meisterhafter Weg, die ‚Blue Notes‘ des Jazz in den Nahen Osten zu tragen."

Norddeutscher Rundfunk

Ralf Dorschel

"Die Melodien der arabischen Musiktraditionen bilden die Basis. Sie wandeln sich im Interplay zu einer wunderbaren Musik, die den Spirit der Welt beruhigt."

Kulturtipp

Pirmin Bossart

"Der tunesische Oud-Virtuose und Komponist Anouar Brahem hat seit Anfang der 1990-er Jahre auf seinem Haus-Label ECM in unterschiedlichsten Besetzungen ein Dutzend exzellenter Alben veröffentlicht. Folglich sind in seinem Fall die Erwartungshaltungen der Fans vor Neuveröffentlichungen besonders hoch, aber selten dürften sie so voll erfüllt oder gar noch übertroffen worden sein wie nun mit ‚Blue Maqams‘. […] In den neun Brahem-Kompositionen, die sich von wenigen Ausnahmen abgesehen zwischen acht und elf Minuten Länge bewegen, stellen Holland und DeJohnette ihre über Jahrzehnte gewachsene souveräne Technik und ihr unglaubliches Einfühlungsvermögen gepaart mit einem unerschöpflichen musikalischen Einfallsreichtum in den Dienst der Sache. Holland lässt seinen Bass singen, dass es eine Freude ist, und DeJohnette erzielt mit sparsamsten Mitteln größte Wirkung. Brahem und Bates brillieren mit wunderschönen Soli, umgarnen sich in subtilen Dialogen und inspirieren sich wechselseitig zu brillanten Höchstleistungen. Arabische Musik und zeitgenössischer Jazz begegnen sich hier absolut auf Augenhöhe, die Akteure schöpfen aus dem Besten zweier musikalischer Welten, ohne die eine oder die andere zu desavouieren."

Kultur

Peter Füssl

"Ein Nordafrikaner, ein Amerikaner, ein Brite und ein britischer Ami steuern ein gemeinsames Vehikel, indem sie sich frei von allen Floskeln und Plattitüden zwischen Improvisation und Meditation einfach der dramatischen Magie des Klangs hingeben."

Stereoplay

Wolf Kampmann

"Der Musik des Oud-Virtuosen Anouar Brahem (Oud ist die arabische Kurzhalslaute) ist schwer einzuordnen und leicht zu verstehen. Man kann sich in ihr ohne Vorausssetzung einrichten wie in einem wohltemperierten Ambiente, wie in einer musique d’ameublement, auch das Missverständnis ‚world music‘ mag für den einen oder andern naheliegen, auch wenn sich der 1957 in Tunis geborene Brahem gegen die Etikette vehement (und zurecht) wehrt. Mit zehn Jahren begann er das Studium der arabischen Musik, bald mit dem legendären Lehrer Ali Sriti. Dann folgte eine sukzessive Horizonterweiterung, auch in Richtung des Jazz, obwohl er sich „weder als Jazzmusiker noch als Jazzkomponisten“ versteht. 1991 spielte er seine ersten Aufnahmen für das Label ECM von Manfred Eicher ein, das in der Folge seine musikalische Heimat wurde und die Entwicklung seiner grenzüberschreitenden Musik mit bestimmte: Produktionen mit Musikern wie Jan Garbarek (‚Madar‘, 1994), Richard Galliano und François Couturier (‚Khomsa‘, 1995), John Surman und Dave Holland (‚Thimar‘, 1998), auch mit verschiedenen klassischen Orchestern (zuletzt ‚Souvenance‘, 2014) – Brahem hatte den Kopf im kreativen Wind, woher immer der wehte, und verriet doch nie seine Ursprünge, schon gar nicht durch eine Auflösung der Konturen im Sinne einer parfümierten exotischen Allerweltsmusik. Seine meditativen Räume laden die Partner zu intensiven, weit gespannten Atembögen, aber nie zu beliebigen Ego-Trips ein – dafür besteht er zu rigoros auf der steten Anbindung an die komponierten Vorgaben. So auch auf seinem jüngsten Opus ‚Blue Maqams‘, an dem sein grosser alter Partner Dave Holland am Kontrabass beteiligt ist, der fabelhaft diskrete, feinsinnige, differenzierte Jack DeJohnette an einem schwebenden Schlagzeug und der britische Pianist Django Bates, bei aller technischen Brillanz mit Erfolg darauf bedacht, die Räume der geradezu skrupulös sparsamen Partner nicht pleonastisch zuzuschütten. So entsteht eine hoch poetische, nie gefühlige, immer herzerwärmende eigene Musik zwischen den Kategorien und zwischen den Welten. A very special Kind of Blue."

Die Weltwoche

Peter Rüedi

"Die Geschichte der Annäherung zweiter musikalischer Sphären in einem Balanceakt der Schönheit."

Die Zeit

Stefan Hentz

"Brahems Begleiter sind diesmal der britische Bassist Dave Holland (71), mit dem er schon vor 20 Jahren gespielt hat, und der legendäre Drummer Jack DeJohnette (75), der 1969 auf Miles Davis‘ epochalem Album ‚Bitches Brew‘ mitwirkte. Hinzu stieß, eine Idee Eichers, Pianist Django Bates (57). Der Brite spielt erstmals mit Brahem – ein temperamentvoller, kantiger Kontrast zu dessen langjährigem Partner am Klavier, Francois Couturier. Das wirkt sich aus – neben verträumten, meditativen Passagen wie im Titelstück und in ‚La Nuit‘ finden sich expressive, energiegeladene Improvisationen […] Ein Prachtalbum, das sich jeglicher Kategorisierung entzieht."

Sächsische Zeitung

Jens-Uwe Sommerschuh

"Ein sehr versöhnliches Album unter der Regie des Münchner Klangmeisters Manfred Eicher."

Literaturspiegel

Janko Tietz

"Eine Platte mit betörender, geradezu hypnotisierender Musik."

Südwestrundfunk

Johannes Kaiser

"Es ist ein Meisterwerk, weil die Blue Notes des Jazz vielleicht noch nie so schlüssig und unbeflissen mit der modalen Musik Arabiens verbunden wurden. Hier treffen sich Freiheit und Ehrfurcht vor der Tradition wie selbstverständlich."

Berner Zeitung

Ulrich Steinmetzger

"Die perfekte Balance zwischen Komposition und Improvisation […] So startet ‚Bom Dia Rio‘ den musikalischen Dialog mit sprödem Charme, solo auf der Oud. Hollands Bass setzt mit einer kleinen, flinken Figur ein. Der Pianist streut ein paar Akkorde ein, nimmt die Melodie auf und DeJohnette grundiert dies alles mit feinsten Pinselstrichen an Becken und Trommeln. Ein Meisterwerk der Entschleunigung."

Badische Zeitung

Andreas Collet

"Poesie ist das Kennwort dieser Begegnung, die atmosphärisch mit leisen Becken-Crashs in ‘La Nuit’ wandelt, wobei ein Klaviermonolog sogar atonale Bereiche berührt. Der Titelsong hat fast Popqualitäten und ‚Persepolis’s Mirage‘ einen intensiven Ostinato-Groove."

HiFi & Records

Hans-Dieter Grünfeld

Accolades

De Klara's Classical Music Awards, "Best international CD – World" (Belgium)

Editor’s Pick, "DownBeat" (USA)

Best Releases of 2017, "All About Jazz" (USA)

Top 20 Jazz Albums of 2017, "Jazz Wise Magazine" (United Kingdom)

5★ "Evening Standard" (United Kingdom)

4★ "Stern" (Germany)

Choc, "Jazz Magazine" (France)

Choc, "Classica" (France)

5/5 "Dagens Nyheter" (Sweden)

Palmares / 10 albums jazz 2017, "Le Devoir" (Canada)

5★ "The Sydney Morning Herald" (Australia)

Background

Three brilliant improvisers join Tunisian oud master Anouar Brahem in this album, recorded in New York in May 2017. For Brahem and Dave Holland the album marks a reunion: they first collaborated 20 years ago on the very widely-acclaimed Thimar album, a trio recording with John Surman. Brahem meets Jack DeJohnette for the first time here, but Holland and DeJohnette have, of course, been frequent musical partners over the last half-century, beginning with ground-breaking work with Miles Davis: their collaborations are legendary. British pianist Django Bates also rises superbly to the challenge of Brahem’s compositions. And Anouar in turn is inspired to some of his most outgoing playing.

For Anouar Brahem, it’s the work itself that sets a direction. He addresses the question of context and setting only as his music “emerges”: “I simply began in my usual way”, he writes in his liner note for Blue Maqams. “Letting the ideas come in of their own accord, with no tendency one way or another in terms of style, form or instrumentation.” He worked on several sketches in parallel, “and what emerged first and then really began to take shape was my desire to blend the sounds of the oud and the piano once again, soon followed by my wish to associate this delicate instrumental combination with a real jazz rhythm section.”

Although he has never harboured ambitions to be a jazz player, Anouar has long felt a sense of solidarity with the music’s practitioners: “I first started listening to jazz when I was a teenager living in Tunis in the 70s. At the time, I was passionately devoted to the traditional Arab music I’d had the good fortune to study under the great master Ali Sriti. Paradoxically, I was [also] full of curiosity about other forms of musical expression. The aesthetics of jazz were very different to those of Arab music, but I was attracted by this music that took me into a completely different world, one I felt close to as well. Undoubtedly there is a kind of spontaneity in Arab music, a way of playing that allows musicians to go deep into their own feelings and take some liberties with the original score through improvisation; and perhaps this somehow echoes what happens in jazz.”

Brahem began to play with jazz improvisers in the 1980s, with recorded collaborations beginning the following decade. The album Madar (1992) brought Anouar together with saxophonist Jan Garbarek and tabla player Shaukat Hussain, while Khomsa (1994) found him reworking compositions written for film and theatre with improvisers including François Couturier, Palle Danielsson and Jon Christensen. Thimar (1997), with Dave Holland and John Surman, marked a major breakthrough in the space between the traditions, with the participants finding a shared musical language. Blue Maqams takes this notion further. The “maqams” of the title refers to the sophisticated modal system of Arab music, perhaps rendered kind of blue by the participating improvisers.

Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette have played together on a number of ECM recordings including four albums with John Abercrombie in the Gateway trio, Kenny Wheeler’s Gnu High and Deer Wan, and George Adams’s Sound Suggestions. Brahem first encountered this mighty bass and drums team live in Zurich in the early 1990s, when they were performing with Betty Carter and Geri Allen. “This charismatic rhythm section left a very powerful impression.” Playing live with Dave Holland, on tours with the Thimar trio, was an experience Brahem cherished. “I often told Dave that his playing gave me wings as a soloist. And we spoke, too, about doing more recording. It was a matter, though, of waiting for the right material. But once I’d thought about Dave for this new album, it was very natural to think about Jack, too. It’s an immense privilege to have their participation.” Bringing the jazz drum kit and the soft-singing oud together presents specific dynamic challenges: “I was aware, when I saw that the music would need drums, that this would indeed be challenging, but I also felt that if anybody could address this creatively, it would be Jack DeJohnette, who is one of the most sensitive and subtle drummers. He can move as delicately as a cat, with such a graceful and flowing rhythm.“

Finding the right pianist for the project took longer. “For several months, I listened to a considerable number of players and had many long discussions with Manfred about the style I thought this record needed. Finally, he asked me one day to listen to a recording he’d just made with Django Bates…” [This was The Study of Touch, with Bates’s Belovèd trio with Petter Eldh and Peter Bruun, scheduled for release in November.] “I was highly impressed by Django’s mixture of virtuosic musicianship and lyricism. In the recording studio, I discovered several qualities in Django, not only his dazzling piano technique, but also his creative and inventive powers and his outstandingly strong proposals. He does some absolutely magnificent things on this recording that always bring something new and unusual to the score.”

Balancing freedom and faithfulness to the score is crucial for Anouar Brahem: “I like each piece to keep its own identity in and through written music. The musician’s role is to fit into this universe and express himself inside the framework of this identity... It’s important for me to keep the true universe of each piece. An important part of our group work has been about this aspect – working together to find the right balance between composed and improvised music. For even in composed pieces or passages where I leave no room for personal interpretation, I like the music to sound as though it surges forth in an inspired, improvised flow.”

The music for Blue Maqams was written between 2011 and 2017, with the exception of two pieces, “Bom Dia Rio” and “Bahia”, both of which were composed in 1990, and revived for this project. Long-term Brahem listeners will be familiar with “Bahia”, a version of which can be heard on Madar.

Liner note

"I simply began in my usual way. Letting the ideas come in of their own accord, with no special tendency one way or another in terms of style, form or instrumentation. Without my realizing it, what emerged first and then really began to take shape was my desire to blend the sounds of the oud and the piano once again, soon followed by my wish (and something of an attempt at the impossible!) to associate this delicate instrumental combination whose balance and dynamics always require particularly fine treatment to include them, with a real jazz rhythm section.

When it came to the choice of musicians and who would play double bass and who’d be the drummer for this project, it didn’t take me long to decide. Dave Holland came to mind right away. Ever since I met him twenty years ago to make my album Thimar with him and John Surman, I’ve let it be known that I would like to record with him again. We often talked about the possibility when we met on tours – I told him that playing with him had ‘given me wings’ – but it was also a question of waiting for the right material. I’m really delighted that this record has provided the occasion for a reunion with this immense double bass player.

As for the drums, and even though I’d never had the chance to work with him, one of the only players I could imagine capable of sufficient finesse and subtlety to adapt his style to the poetry of the oud, was Jack DeJohnette. It so happens that he already knew my music and accepted my invitation immediately. I knew he was a phenomenal musician – and in fact, he’s a true feline, with a wonderfully elastic and graceful rhythm! Over and above that, I discovered an exceptional human being, very open-minded, full of curiosity, and extremely modest. On this recording, each time he plays, he does so with a melange of the necessary and the natural, blending his years of experience with an almost childlike freshness and spontaneity.

It took me much longer to find the pianist. I’ve been playing with François Couturier for more than 32 years, so he’s very familiar with my music and a close friend too – that’s another strong argument. So it was natural to think of him first, but then I quickly felt this project required me to break with my old habits and venture out onto new territory. For several months, I listened to a considerable number of players and had many long discussions with Manfred about the style I thought this record needed. Finally, he asked me one day to listen to a recording he’d just made with Django Bates, unknown to me then, but I was highly impressed by his touch and style, a mixture of virtuosic musicianship and lyricism. I decided to include him on the project.

In the recording studio, I discovered several qualities in Django, not only his dazzling piano technique, but also his subtlety, his creative and inventive powers and his outstandingly strong proposals. He does some absolutely magnificent things on this recording that always bring something new and unusual to the score.

As the whole pattern of the recording began to emerge, I became aware that for me, it would be a chance to come back to my own story and its links to jazz, as well as a way of celebrating my love of this major musical genre born in the 20th century.

I first started listening to jazz when I was a teenager living in Tunis in the 70s. At the time, I was passionately and exclusively devoted to the traditional Arab music I’d had the good fortune to study under the great master Ali Sriti. My sole ambition was to become a good musician so I could take part in restoring the reputation of this tradition. Paradoxically, I was full of curiosity about other forms of musical expression and longing to discover them. Apart from the great traditions of Indian, Turkish and Balkan music that had always fascinated me since my childhood, once I was seventeen, I began turning to more contemporary genres, one of which was jazz; it was soon obvious that this was what attracted me most. The aesthetics of jazz were very different to those of the Arab music I was often involved with. I didn’t always understand what jazz musicians were trying to express, but I was attracted by this music that took me into a completely different world, one I felt close to as well. Undoubtedly there is a kind of spontaneity in Arab music, a way of playing that allows musicians to go deep into their own feelings and take some liberties with the original score through improvisation; and perhaps this somehow echoes what happens in jazz.

What also drew me to jazz was the fact that in spite of its popular origins, this music, relatively young in terms of the history of music, has been able to reach such a high level of sophistication, so much so that it now has a central role in the music of today. Arab music with its centuries-old, rich and highly sophisticated traditions, seemed to me to be caught up in some sort of conformist conservatism in comparison, whereas in jazz, I found the perfect example of music that belonged to its epoch without denying its own nature, and this fascinated me. Not only that: jazz was associated with ideas of transgression and freedom for me – and at the time, I already believed no creative work could exist without breaking the rules somewhere. Jazz was an extraordinary field for experimental possibilities and at the same time, fruitful ground for intermixing and cross-breeding. It was also a language naturally open onto different cultures and I felt I could find my place there… I knew I would never be a jazz musician but I felt as though I belonged to that community spirit.

So at the age of seventeen, it was jazz that broadened my horizons and forged my desire to begin committing my music to what might be called modernity – and this without denying my status as a learner, my previous experience and my culture.

But I had always refused to take any intellectual steps based on will-power alone. Where artistic creation is concerned, I always prefer to rely on my intuition. In the very early 80s, when the idea emerged of assimilating instruments from other cultures such as jazz or Indian music into my compositional process, I was the first to be astounded by it. But then I decided to go and live in Paris, hoping to meet musicians from other backgrounds. This was the time when I introduced musicians such as François Jeanneau, François Couturier, Jean-Louis Matinier and Barbaros Erköse into my projects for the Tunisian stage and cinema. Some of these musicians would later accompany me on my ECM recordings.

I only met Manfred Eicher at the end of 1990, when he opened the doors of his label to me. But curiously, I didn’t take on any jazz musicians for my first recordings on ECM. No doubt because I wanted to keep my distance from the so-called ‘world music’ that was fashionable then, a kind of hybrid genre where quite a number of musicians turned out to be opportunists, who changed their colours and went in that direction. I didn’t want to be one of them. My first recorded encounter with a jazz musician happened a little later on the album Madar, which I made with Jan Garbarek in 1992. The rest is part of my story with the ECM label…

Most of the pieces on this record were composed between 2011 and 2017. I have also re-introduced two old compositions ‘Bahia’ and ‘Bom Dia Rio’ dating from 1990.

As I so often do, I’ve tried to compose a score that leaves plenty of room (more or less, according to each case) to improvisation and real freedom in the interpretation of a piece. For all that, I still feel it’s equally important to remain faithful to the score, staying as close as possible to what is written down. I like each piece to keep its own identity in and through written music, i.e. a written score; the musician’s role is thus to fit into this universe and express himself inside the framework of this identity. If the place given to improvisation or free interpretation is too ‘open-ended’, I think the music risks losing its true nature. In that case, everything is alike. It’s important for me to keep the true universe of each piece. For jazz musicians, this idea can sometimes seem a little too directive and there were some fierce discussions during the recording. An important part of our group work has been about this aspect – working together to find the right balance between composed and improvised music. For even in composed pieces or passages where I leave no room for personal interpretation, I like the music to sound as though it surges forth in an inspired, improvised flow. The first time my wife to whom I dedicated this album listened to the music, she told me she found it both modern and traditional at the same time. I tend to think she’s right about this and moreover, this is the first time I’ve included some taqsim (a traditional form of improvised solo) within some composed pieces…

During the actual recording, I can sometimes be too concerned about my own playing as a performer. It’s like directing a film and being an actor in it too, I often attach too much importance to the imperfections of a take, thus risking losing an overview of the whole thing, which is vital if we are to make the right choices. This is where Manfred’s role is essential.

As well as knowing how to talk to the musicians to untangle or cut through any form of conflict, his careful way of listening and his judgement are invaluable. He has an extraordinary capacity for recognizing the most inspired takes and when he’s behind the console, he becomes an extremely sensitive sculptor of sound. And what’s more, he hears the music as it unfolds in a dramatic, theatrical sense and I always have the impression we speak the same language. Over time, we’ve developed a beautifully close understanding together. His presence and way of listening never alter the nature of the music; rather they bring out its best qualities."

Anouar Brahem