Anouar Brahem

Anouar Brahem, oud

François Couturier, piano

Jean Louis Matinier, accordion

About

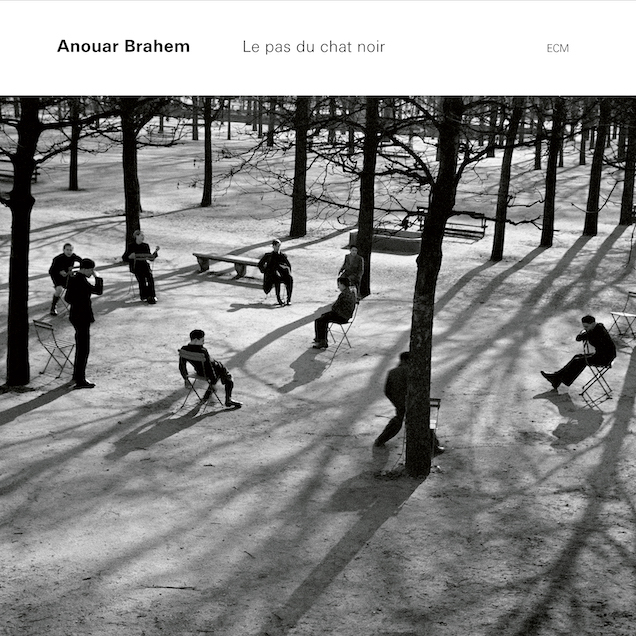

Hypnotic, magnetic new album by Anouar Brahem which adds a new dimension to our knowledge of this exceptional Tunisian musician. Le Pas du Chat Noir gives the clearest indication yet of the work of Brahem as composer and features a spacious "chamber music" that resonates with the freshness of improvisation.

The instrumentation is unique: oud, piano, accordion. Brahem's writing for this combination is highly evocative, meticulously controlled and sparse. Half of the magic, as he notes, resides in the not-played, in the marvellous mingling of overtones, sounds that rise from the piano to blend with the warm tones of the oud and the breath of the accordion's bellows.

Tracks

Le Pas du Chat Noir

De tout ton Cœur

Leila au Pays du Carrousel

Pique-Nique à Nagpur

C'est Ailleurs

Toi qui Sais

L'Arbre qui Voit

Un Point Bleu

Les Ailes du Bourak

Rue du Départ

Leila au Pays du Carrousel, var.

Déjà la Nuit

Press reaction

"The album is at once an extension and an audacious departure from the tradition of the oud. Despite his formidable knowledge of the maqarnat, an ornate system of modes that anchors Arabic music, he seldom bases his improvisations directly on the maqams. His phrasing is pure and uncluttered, expressing itself through silence nearly as often as sound. ...Composed of elegantly flowing lines and somber, breathlike silences, the music shimmers with the overtones of the piano. ... Mr. Brahem bases several of the tunes on spare, broken chords, repeated in the childlike manner of Satie. Simple though they are, however, they contain beguiling Arabesques. The three musicians rarely appear at once, performing as a trio on only seven of the album's 12 tracks. For the most part, you hear duets - piano and oud, oud and accordion, accordion and oud. The musicians often double each other's lines, but seldom in unison, which enhances the music's intimacy while producing a floating, echo effect.If every band projects "an image of coummunity," as the critic Greil Marcus once suggested, then Mr. Brahem's trio - part takht, part jazz trio, part chamber ensemble - evokes a kind of 21st century Andalusia, in which European and Arab sensibilities have merged so profoundly that the borders between them have dissolved. The image may be utopian, but its beauty is undeniable."

The New York Times

Adam Shatz

"The album is like a sad rhapsody, full of shadowy mirages and blue echoes, the prevailing melancholy not dour and heavy but rather light and cloudy. Names like Satie, Debussy, Mounir Bachir, even Eno in acoustic mode keep flashing across your mental screen as you listen. This is academy music with no clothes on, naked and awkward, honest and beautiful. Shut your eyes and you could be in the port of Dar el Baida, a seagull swooping over a grey-blue sea and huge cranes and rusty hulled freighters in the background, the light and forgetful breeze brushing your cheek. Le pas du chat noir features uncontrived performances of cat-like agility - soft, bright-eyed and magical. It is a brilliant piece of work."

Songlines

Andy Morgan

"Who would have thought that the supremely subtle oud could be featured on a recording with piano, that most dominantly Western of instruments' Meticulously arranged and ideally, gorgeously recorded, Le pas du chat noir features Tunisian oud virtuoso/composer Anouar Brahem in a fresh setting conceived at the keyboard and then realized with pianist François Couturier and accordionist Jean-Louis Matinier. The result is as redolent of the French minimalism of Satie and, even more so, his Catalan successor Mompou as it is of traditional Arabic music. There is a hushed, highly concentrated quality to this Pan-Mediterranean musical "haiku", with the notes purified down to their absolute essence. The entire package-music, sound, cover design - is ECM at its best. As much as any of the label's "crossover" hits, this album brims with appeal for all who have an ear for the best in music."

BillBoard

Bradley Bambarger

"A record of astonishing harmonic richness, Le pas du chat noir attests to Brahem's unexpected devotion to the piano as a compositional tool and forces some retrospective recognition of how classically pianistic a lot of his music has been down the years. The oud here takes its place in a rich and constantly shifting context, with the two keyed instruments creating contrasting textures and environments for Brahem's gorgeous melody lines. ... This is a consistently rewarding and very surprising record. Ask me a year from now and I'll be finding new things in it."

Jazzreview

Brian Morton

"Dramatiques, sereines, légères, profondes... Il est difficile de qualifier les atmosphères qui s'en dégagent. En un mot, voilà une musique pleine, qui n'a pas peur du vide, du quasi-silence, où la note juste est conservée, sans excès de minimalisme étriqué. ... Sans jamais perdre la direction qu'il s'est choisie, ce disque réaffirme le plaisir et sa sensualité de ce musicien expert, son goût pour la formule du trio, format qu'il creuse en renouvelant constamment l'instrumentation."

Jazzman (Choc Jazzman)

Jaques Denis

"Arabische, maghrebinische oder gar Weltmusik - derlei Schubladen waren für den tunesischen Oudvirtuosen Anouar Brahem von jeher zu eng. Bestes Beispiel: das Trioalbum Thimar mit John Surman und Dave Holland. Jetzt hat er mit dem französischen Pianisten François Couturier und dem Akkordeonspieler Jean-Louis Matinier ein noch weitaus ungewöhnlicher instrumentiertes Trio zusammengestellt. Die Stücke entwickelte er am Klavier. Erst viel später fand sein eigentliches Instrument, die arabische Laute Oud, ihren Platz in dieser sparsamen Kammermusik voller Stille, Poesie und atmosphärischer Nähe zu Erik Satie, in der das Akkordeon gleichsam die Rolle einer "inneren Stimme" übernimmt. Grandios."

Fono Forum

Berthold Klostermann

"Diese stille, anrührende Musik lebt von wechselnden Dialogen, die arabische Gelassenheit in rhythmischer Vertracktheit mit europäischer Kammermusik von Bach bis zur Klassischen Moderne in Einklang bringen. Jean-Louis Matinier zieht die Klänge seines Akkordeons mit einer bittersüßen, vibrierenden Eleganz; Klänge, die in ihrer reduzierten Intensität wie ferne Schwingungen des innersten Wesens französischer Muzettes wirken. Dazwischen weben sich die Töne der Oud, die zart von François Couturier am Flügel aufgegriffen und mit sutiler Raffinesse verdoppelt werden. Intime Zwiegespräche entwickln sich, eine einsam schwingende Klaviersaite ruft ein Echo auf der Oud hervor, es entsteht ein Frage-und-Antwort-Spiel von geradezu hypnotischer Kraft."

Stereoplay

Sven Thielmann

Accolades

Top of the World / Editor's Choice, "Songlines" (United Kingdom)

Choice of the Month, "BBC Music Magazine" (United Kingdom)

Die Audiophile, "Stereoplay" (Germany)

Critics Choice, "Jazz Zeitung" (Germany)

ƒƒƒƒ "Telerama" (France)

Recommended, "Classica" (France)

Choc, "Jazzman" (France)

Five Essential Albums of 2002, "Jazziz Magazine" (USA)

Background

Unique instrumentation – oud, piano, accordion – is only part of the allure of Anouar Brahem's exceptional new album. The pieces that make up Le Pas du Chat Noir came into existence under unusual circumstances...

After the intense and emotionally draining experience of recording the "transcultural" album Thimar with John Surman and Dave Holland in 1997, an album on which jazz improvisation was cross-referenced with the modes of Arab music, Brahem found himself, for the first time ever, reluctant to play the oud.

"I stopped playing the oud for quite a long time," Brahem recalls. "But it was important to have a contact with the music. I didn't stop listening to music, nor did I stop writing. I have a piano in my atelier in Tunis, and I began to compose on it." In the past, Brahem has quite often turned to the piano when writing music for film. "The sound of the oud has an identity and a specific Arabic character. The piano gives me another sonority which I like very much, and which doesn't have those associations. I'm not really a piano player, but I was using the instrument as a pen – to write modal music. So gradually some material came together – themes, melodies – and I could see that there was some kind of unity there, but I had no plans for the music."

Brahem played some of the material for ECM producer Manfred Eicher, who encouraged him to develop his piano music further. But it took a couple of years for the music to find its current form and for two other musicians to become part of it, and for the oud to re-enter and find its place.

Pianist François Couturier has worked on projects with Anouar Brahem since 1985, and was Brahem's first choice as pianist. "When playing the melodies," Brahem says, "I sometimes sang with the piano, and I realized I also needed another sound, a sustaining sound, more linear." Cello was briefly considered, then Brahem thought about the work of accordionist Jean Louis Matinier, a musician he had first met in a recording studio ten years earlier. He had subsequently followed Matinier's collaborations with Gianluigi Trovesi and with Renaud Garcia-Fons. "The grain of the accordion sound is important, but more than that Jean-Louis understood the real place for his instruments: he didn't want to do more than the music requires. And this discretion gave strength to the performance." As Brahem says, Matinier "carries the inner song of the music."

Despite the wealth of experience that both Couturier and Matinier have amassed, they found the clearly etched, sparse music, the "silent songs" of Le Pas du Chat Noir difficult to play. "The music is very precisely written, and it's important to respect all the tempo markings and pianissimos, but at the same time the interpretation needs sensitivity and to play as if you were improvising. So you have to be very focused. With the elasticity in the tempos – sometimes it's accelerando, sometimes it's rallentando, you have to be very aware of maintaining internal tension."

In this spacious music, the tones that are not played are also of critical importance. "I told François to recognize that the overtone is sometimes more important than the tone. The reverberation of the harmonics after the notes is a big part of this music. The overtones of the piano in this music sometimes remind me of the overtones of the santour [hammered zither] in the music of Iran," says Brahem.

"Manfred also found the right place to record this music [the Radio DRS Studio in Zürich] with an excellent piano and a great acoustic," he continued. "It was very helpful to be able to record without headphones. We took our time to record, and mixed some months later – that was also crucial, finding the right balance between the instruments. We also took a long time determining the order of the pieces, too. It was all a careful, step-by-step process."

To what category does this music belong? In terms of Brahem's work it has the closest atmospheric affinities to Barzakh and Conte de L'Incroyable Amour, yet it is very different, too. Some listeners have spoken of parallels with the work of Satie, Ravel, Debussy, Mompou, or even Arvo Pärt. "I don't know enough about European piano repertoire to make those references intentional," says Brahem. "But I was once very touched by some music of Satie that I heard, perhaps ten years ago. It seemed not western, not oriental, somehow non-temporal. This music really spoke to me. And after I had written a few themes, I thought perhaps there might be a connection..."

Brahem hopes the album will not be relegated to "world music" columns or browser bins: "I'm increasingly irritated by the term. It's not a movement, it's not an aesthetic, it's nothing more than a marketing tag for stores in the west, which throw together completely unrelated music. The equivalent, from my perspective, would be to go into a store in Egypt and find Boulez, Keith Jarrett and Britney Spears all marketed as 'world music.' One of the things I appreciate about being at ECM is that I've never been treated as an exotic appendix of the catalog. I'm making my own kind of contemporary music on a contemporary music label."

Liner Note

"These pieces emerged from the keys of a piano. Still affected by the powerful emotion of the encounter, and the exhaustion which followed the recording of Thimar, I set the oud aside for a few months, something that had never happened to me before. It was as though the music came from there, from the space created by that pause. As though it was the very expression of that lack. I did not start out with the intention of writing for the piano. It just replaced the oud. In fact, I used the piano as an instrument of modal writing. I have always had a piano in my studio.

Manfred Eicher, to whom I had played a few initial themes in Carthage, gave me great encouragement to develop them with a view to a recording. I composed some other pieces. Still for solo piano. The piano was the main character, the sole protagonist. It was only later on that the oud came in. It joined the piano gradually, discreetly at first, then it assumed its place. It was a long time, on the other hand, before the idea of integrating the accordion came into my head, whereas it seems obvious to me now. It’s like this music’s inner song.

In particular I would like to thank François Couturier, my long-standing friend and accomplice, and Jean-Louis Matinier, both of whom worked tirelessly to communicate the universe of this music, in an interpretation extremely alert to nuances and tempos, and to the balance between inner tensions and falls. A tempo passed on to me by the movement of a tree I could see from my window, swaying gently in the breeze."

Anouar Brahem