Anouar Brahem

Anouar Brahem, oud

John Surman, bass clarinet and soprano saxophone

Dave Holland, double-bass

About

"... I saw, then, in a dream, a tree of an incomparable verdant freshness, beauty and magnitude; on this tree three kinds of fruit were growing that bore no resemblance to the fruits of this world and were plump like a virgin’s breast: a white fruit, a red fruit and a yellow fruit, shining like stars on the green base of the tree ..."

Rabia Al Adawiya (c. 714 – 801 CE)

A strikingly attractive "transcultural" project initiated by Tunisian oud virtuoso Anouar Brahem, who is both an innovator and a traditionalist in the deepest sense (he has been credited with "restoring the sovereignty of the oud" in Tunisian music). There is no glib fusion of traditions on Thimar but rather a coming together of three very distinctive musicians who sacrifice none of their individuality in the search for common ground. Arab classical music and jazz are the reference points here, but Anouar Brahem, John Surman and Dave Holland meet as improvisors not limited by genre definition.

Tracks

Badhra

Kashf

Houdouth

Talwin

Waqt

Uns

Al Hizam al Dhahbi

Qurb

Mazad

Kernow

Hulmu Rabia

Press reaction

"Thimar shows that ECM is still at the front of contemporary music-making. lt's a perfect example, too, of how different musical traditions - jazz and Arabic - can be combined to create something unprecedented, unique ... Lack of percussion could have resulted in music ethereal to the point of vapidity, but the depth of interplay between the musicians ensures that even the most exquisite Iyrical touches are firmly earthed. Wonderful."

Deutsches Allgemeines Sonntagsblatt

Geoff Dyer

"ln Brahem's hands the oud is a staggeringIy versatile instrument. It can sound like a Spanish guitar or even a sitar as he creates mostly unhurried lines, whether of contemplation or rapture. Surman sounds perfectIy at home, charming snaking lines and bent notes from his horns, while Holland contributes his trademark, marvellously thick sound and outstanding solos."

Sydney Morning Herald

John Shand

"Jazz album of the month is probably Thimar by Anouar Brahem on the ECM label, whose imprint rivais M & S as a sure sign of quality in the marketplace... The result is contemplative yet intensely rhythmic music in which Holland and Surman contrive to sound surprisingly Arabic while in turn Brahem swings most convincingly, emphasising that jazz's African roots were tllem selves partly derived from Arabic sources."

The Independent

Phil Johnson

"Music of minute colouristic detail, a fusion of contrasting cultures without a sacrificing of musical identity. The album could ID well be the best of 1998. More and more, it seems, jazz is finding ways of renewing itself from world rhythms."

The Observer

Stuart Nicholson

"La musique d'Anouar Brahem a atteint aujourd'hui un degré de maturité stupéfiant... D'un calme souverain, d'une puissance subtile, les mélodies d'Anouar Brahem ont déjà, par six fois, croisé le chemin d'ECM avec des musiciens aussi divers que Galliano ou Garbarek... Avec Thimar, le magicien du Oud nous propose une nouvelle rencontre stimulante avec John Surman et Dave Holland. Des climats magiques résultent de cet échange... Chacune des onze plages de ce disque s'écoutent comme on regarde une miniature : elles nous racontent autant d'histoires et de secrets, sans jamais lasser... Une merveille. Tout simplement."

Classica

Bertrand Dermoncourt

"Un disque à la beauté aussi terrassante ne se rencontre pas tous les jours. Au-delà de la superbe rencontre conjoncturelle magnifique, Thimar illustre, avec une maîtrise technique et un engagement émotionnel rares, le caractère essentiel de la musique : l'universalité...

Ce disque inattendu est un chef-d'oeuvre."

Répertoire

Jean Pierre Jackson

"Es gibt Platten, die einen einsaugen . die momentane Stimmungen aushebeln und die Gefühlswelt neu ordnen . Thimar ist so ein Zauberwerk. Der tunesische Meister an der Oud hat mit dem Jazzbassisten Dave Holland und dem Klangpoeten und Saxophonisten John Surman eine Produktion geschaffen, die Körper, Geist und Seele gleichermaßen satt macht. Das ist keine zusammengerührte Soße namens Weltmusik, sondern eine Verbeugung eines zeitgenössischen kammermusikalischen Trios vor der hohen Kunst der klassischen arabischen Musik."

Süddeutsche Zeitung

Geseko von Lüpke

"Behutsame Kunst, die das Gegenteil dessen ist. was ais "Weltmusik" sonst in den Regalen steht. Surman, der keltische Melomane, und Holland, der singende Fundamentalist (er sorgt in diesem schlagzeuglosen Trio auch für die rhythmischen Verstrebungen) eignen sich Brahems ziemlich trickreiche arabische Musik so an. dass wir sie ganz einfach hören; nirgends ächzen die metrischen Wegweiser, es herrscht eine große Gelassenheit und Konzentration aufs Wesentliche. Substanz, kein Parfum."

Weltwoche

Peter Rüedi

"Die hochstehenden Konversationen der drei inspirierten Musiker lassen sich nicht klassifizieren : kein Jazz. keine reine Folklore, keine modische Weltmusik. Sondern eigenständige. stimmungsvolle Klange ohne grossstädtische Aggressionen. Aber in jeder Sekunde spannend und innovativ."

Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Nick Liebman

"Es braucht nicht viel, um eine Musik zu entwickeln, die voiler Farben schillert . Ein paar Melodielinien vielleicht, einige harmonische Schnittmuster, eine Handvoll Rhythmisierungen . Und natürlich braucht es Musiker, die über das Können und die Ruhe verfügen, die kargen Zutaten so zu verrühren, Baß sie Energien freisetzen . Anouar Brahem, der in der traditionellen arabischen Musik fundierte Oud Spieler aus Tunesien, ist so ein Musiker. Dave Holland, der Heilige vom Kontrabaß, sowie der ewig unterbewertete britische Saxophonist und Baß klarinettist John Surman sind es auch . Kategorien wie Jazz haben sie langst hinter sich gelassen und spielen nun eine universale mprovisationsmusik. Eine Musik, die in ihrer Ruhe ausdrucksstark ist. in ihrer opulenten Sch6nheit reif und in ihrer Gelassenheit neugierig."

Deutsches Allgemeines Sonntagsblatt

Stefan Hentz

"Eine Combo ist im besten Falle ein Kollektiv von großen Solisten, deren Zusammenspiel etwas ganz Neues ergibt. In dem die Kunst der einzelnen Musiker noch erkennbar, aber im gemeinsamen Produkt aufgegangen ist. Solch eine Combo bildet der OudSpieler Anouar Brahem mit John Surman, Sopransaxophon und Baßklarinette, und Dave Holland, Kontrabaß. Ihre leise Musik ist geladen mit einer geradezu atemberaubenden inneren Spannung . Die relativ kurzen liedhaften Kompositionen Anouar Brahems, die ergänzt wurden durch einen Titel von Holland, werden teils unisono, teils im kontrapunktischen Miteinander, selten unterbrochen von Soli, gespielt. Mit unaufdringlicher Intensitat. Mit Iyrischer Schönheit. Die sich den Rhythmus ebensowenig wie dem Sound ausliefert. Sondern beide der Melodie nutzbar macht. Da gibt es auch keine Spur von Folklorismus. Surman und Holland gastieren nicht in der arabischen Tradition, sondern dürfen sich in ihrer bekannten Eigenart beteiligen."

Frankfurter Rundschau

Thomas Rothschild

"Ais schiere Sensation begriff das Publikum, wie Hören, Sehen und Agieren zwischen John Surman, Dave Holland und dem tunesischen Oud-Spieler Anouar Brahem, einem ganz unspektakulär grandiosen Virtuosen, musikalische Gestalt gewann. Es war der erste Auftritt der drei nach einer gemeinsamen Studioaufnahme. Die dabei entstandene CD Thimar, dieser Tage veröffentlicht, könnte selbst schon beredte Grundlage werden für eine neue Diskussion über "Weltmusik ", in letzter Zeit allzu oft Hülle ohne Inhalt."

Frankfurter Allgemeine Magazin

Andreas Obst

Accolades

Preis der "Deutschen Schallplattenkritik" (Germany)

4★ "The Guardian" (United Kingdom)

CD of the Year, "Jazz Wise" (United Kingdom)

ƒƒƒƒ "Telerama" (France)

Recommended, "Classica" (France)

4★ "DownBeat" (USA)

CD of the month, "Stereoplay" (Germany)

Background

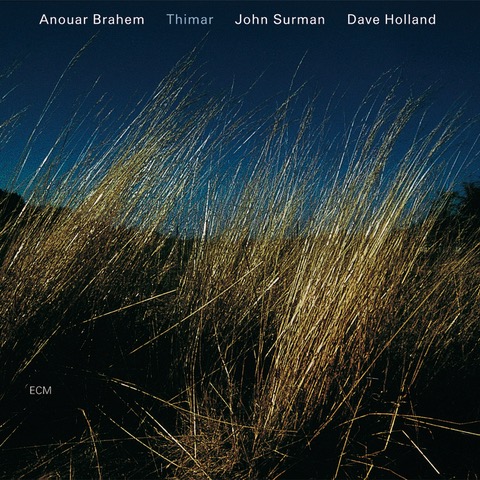

Anouar Brahem, wrote Wolfgang Sandner in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Magazin, "has gone much further than many jazz musicians in energetically seeking out new music." The statement can't be contested, but the oud player from Tunisia has the unusual distinction of being both a progressive musician and a traditionalist in the deepest sense. In his homeland, Brahem has been credited with "restoring the sovereignty of the oud", reclaiming it as a solo instrument in Arab classical music, rescuing it from mere accompanist chores. Simultaneously he has been acclaimed, both within Tunisia's boundaries and beyond them, as an innovator, pioneering very many transcultural projects - of which the appealing Thimar is the latest. It is precisely because Brahem is so strongly-rooted in his own culture that he can risk such endeavours. There is no "fusion" of traditions on Thimar (Arabic for "fruits") but rather a coming together of three very distinctive improvisors, who sacrifice none of their individuality in the search for common ground. Arab classical music and jazz are the reference points here, but Anouar Brahem, John Surman and Dave Holland meet as improvisors not limited by genre definitions.

Brahem studied for many years as a disciple of oud master Ali Sriti in his native Tunis before seeking out points of congruence with other cultures, a search that intensified during his years in Paris (1981-85). He was, however, first heard on disc with an all-Tunisian trio on Barzakh in 1991. This was followed by the collaboration with Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek and the late Pakistani tabla master Shaukat Hussain on Madar and by an album reworking, with an international cast, music Brahem had written for the Tunisian cinema. On Khomsa his partners were Tunisian violinist Bechir Selmi, Swedish bassist Palle Danielsson, Norwegian drummer Jon Christensen, and three musicians from France - accordionist Richard Galliano, keyboardist François Couturier, and saxophonist Jean Marc Larché. "Khomsa is one of the great records of the year," England's The Guardian enthused. "Brahem is at the forefront of jazz because he is far beyond it..." Although Dave Holland and John Surman both contribute compositional material to Thimar, most of the writing stems from Brahem's pen. Two of the pieces were written originally for the Musical Ensemble of Tunis, two more for the Tunisian theater, and one originated as a sketch for the Khomsa ensemble. The majority of the music, however, was prepared specifically for the Thimar session. Performing it was a considerable challenge even for vastly-experienced veterans Surman and Holland.

Dave Holland: "I hadn't known what to expect. Anouar gave us a pile of music the day before the session. There were no bar lines - and of course there were no chords, because that's not a reference point in this music. But there were these complex melodies, and one phrase might have seven beats in it, and another phrase nine. And when John and I started to play this, at first we were stumbling all over ourselves. But we persevered, put some pencil marks on the music, talked about how to approach the structures... At the session, things started to fall into place, as they so often do. The moment impresses itself upon you, and you rise to the occasion. Bringing these traditions together is by no means simple, and I think what we ended up with is music that has real value." It is also music that seems as natural as breathing, far removed from the stilted jazz-meets-the-world projects that litter the discographies.

In terms of "bringing the traditions together", it is interesting that recent musicological studies are beginning to point to the Middle East as a source for jazz that may predate the West African connection. Some scholars now make the case, hypothetical of course, that the African component of early jazz was itself a synthesis, already coloured by centuries of contact with Islamic culture. If true, this would make Brahem's quest for a wider musical context also a matter of reintegration, of recognising something in jazz that is already at the core of his own music.As was the case with Kenny Wheeler's Angel Song, the drummerless music of Thimar places special responsibilities on Dave Holland to shoulder most of the rhythm duties. The demands seem to bring forth some of his finest playing. "With John and Anouar, although my main function was to be accompanist and rhythm player, I felt I was getting support from both of them because of their ability to maintain a sense of rhythm independently..."

The musical context provided by Thimar is an unusual one for both Holland and Surman, but the interests of the two British musicians have always been broader than ”mere” jazz. Few know that in the 1960s Surman, now regarded as the quintessentially English player, made quite extensive studies of Indian music and, of course, improvising from a modal base is by no means a foreign concept for him. Yet while ready to give to the music on Thimar, and to work within Anouar’s framework, Surman also clearly demarcates his own space. The implications of Coltrane’s soprano playing may have led many saxophonists to dabble in quasi-orientalisms, but Surman’s sense of melody derives consciously from his own roots. Significantly, his compositional contribution to the disc is entitled ”Kernow” - old English for ”Cornwall”.

Dave Holland's ability to adjust so quickly to the rhythmic demands of Arab music must be in part attributable to his own experiments with irregular meters. This has been one of the hallmarks of his writing for more than 30 years, and he's suggested his interest in unorthodox time signatures may have had its genesis in his early studies of Bartók (whose indebtedness to Arab music - in the Piano Suite, the Second String Quartet and more - is a matter of historical record...) Holland could also be said to have a philosophical connection to Brahem’s world. The bassist gave notice of his interest in Sufi literature as long ago as 1972, when he titled his first album as a leader, Conference Of The Birds, after Fariduddin Attar’s 13th century epic poem of the same name. Brahem’s own interest in Sufi texts is manifested in the concluding ”Hulmu Rabia”(”Rabia’s Dream”), inspired by the visionary verse of Rabia of Basra (714-801 A.D.), the first female mystic of Islam.

Holland was invited into the session after producer Manfred Eicher played Brahem Angel Song. Brahem: "I listened to that album following the bass. It's like the heartbeat of the music. And Dave's sound is so beautiful. Powerful, but rounded, not at all aggressive or harsh."The oud player first became aware of John Surman's music with the release of the solo album Road to Saint Ives in 1990. "This extraordinary sense of melody that John has...I liked that so much. It touched me very deeply. Since then, I've listened to everything he's done." In 1994, Surman and Brahem toured Japan together but separately, playing opposite each other in concerts to mark ECM's 25th anniversary. "We got to know each other and got along well and talked then about making a record one day. His playing on all his instruments is exceptional, but I especially like the blending of the bass clarinet and the oud. The wood in the sound makes it a very satisfying combination, I think.

"I was really impressed with the engagement of both Dave and John in the making of this album. Collaborations of this kind can be quite...dangerous. Sometimes musicians of different cultures meet only superficially. But they were both concerned to get to the essence of the music."

The Anouar Brahem/John Surman/Dave Holland trio makes its live debut at the ECM New Series Festival in Badenweiler, Germany, at the end of May. In October the trio undertakes a tour through central Europe with concerts at major venues in France, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy.Meanwhile Brahem's reputation as a composer of film music continues to grow. It has been boosted in Germany with the revival of Moufida Tlatlis's Palast des Schweigens, previously listed by Time magazine as one of the ten best films of 1994. Brahem's score is an important component of this "breathtakingly beautiful film" (Süddeutsche Zeitung), and a new audience is now discovering it.